The Fascist Capture

"The history of South Africa has a double importance for white communists in Amerika and other colonial countries."

History as a Guide, Not a Blueprint: South African Fascism and its Importance Today

This essay was written by Zach Medeiros.

If you would like to have your content hosted on Red Voice, contact us at contact@redvoice.news

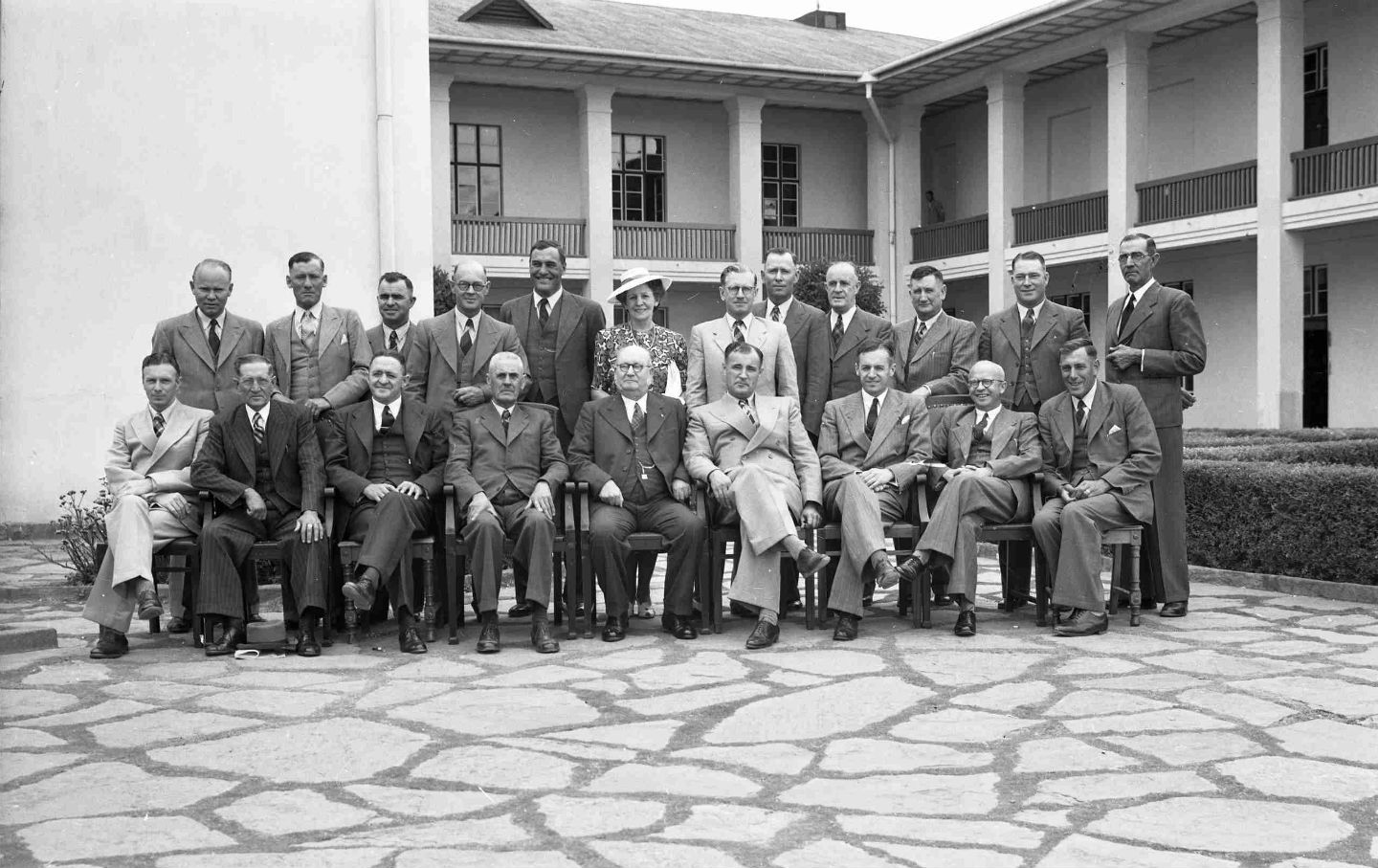

The rise of South African fascism in the 1930s can be seen as a struggle between three factions of the white settler population: a British-aligned group, personified by Jans Smuts, the mainstream Afrikaner nationalists represented by General Hertzog's National Party, and an insurgent radical right, inspired and supported by the Nazis but a product of particular South African conditions. The white liberals were basically meaningless, as usual. All were united in their anti-Blackness and lesser but still powerful contempt towards Asians and mixed race people, but divided by class and national/ethnic allegiances, as well as their approach to democracy- which, in the context of a settler colony, means how to best exploit and repress the "natives."

By the time of the 1948 election and the establishment of apartheid, the National Party and the fascist movements had effectively fused, resulting in an organization that combined aspects of both. Why? Their contradictions proved non-antagonistic. They shared common interests-namely, the construction of an Afrikaner nationalist regime, and hostility towards British imperialism- and what differences they had could be resolved through cooperation. South Africa's ability to weather the worst of the Great Depression, and the relative weakness of the Communists and the African liberation movement, meant that a fully fascist overhaul was unnecessary. Not for capitalists, not for whites in general.

In the end, neither the Nationalists nor their more extreme rivals could hope to progress without the other. Political victory required a synthesis. South Africa's Nazis had to become more parliamentary, and the Nationalists had to become more fascistic. Understanding the nature of South African fascism is not a matter of historical trivia, but something with direct implications for revolutionary struggles today.

What is Fascism?

Before we can examine the impact of fascism in South Africa, we have to grapple with what fascism is and what it is not. More often than not, fascism is flung about freely as an insult instead of as a rigorously understood concept, a rhetorical jab that muddies more than it exposes. Fascism is whatever it is you don’t like. This is a tendency exhibited not just by boneheaded or dishonest reactionaries or liberals, but by too many socialists as well.

The problem is compounded by fascism’s shapeless nature: unlike other political -isms such as liberalism, socialism, or conservativism, fascism has no firm ideological moorings, at least not in the sense of drawn out, reasoned programs or developed philosophical traditions. Historically, fascists have often trumpeted the importance of ideas, only to discard or amend them when expedient. Fascisms in power are quite different than fascisms out of power. Thanks to these characteristics, understanding fascism is no easy task.

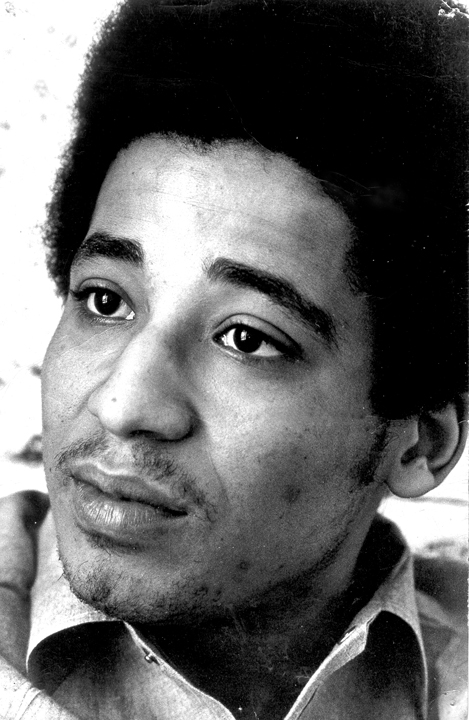

For the purposes of this essay, I will use two conceptions of fascism, as developed by the revolutionary theoretician and organizer George Jackson and the political scientist and historian Robert Paxton. While neither scholar has examined the question of South African fascism in particular, their examinations of fascism as a historical phenomenon are more than developed enough for general application. Both Jackson and Paxton stress that fascism defies easy definition and categorization, and caution others not to settle on a ready-made form that looks the same from nation to nation. Fascism is not a static creature, but a beast in “constant motion, ” a “series of processes working themselves out over time.” Although fascist regimes and movements in different societies have certain similarities, they cannot be reduced to a universal essence. Fascism manifests itself according to general principles and subjective conditions.

As a Marxist-Leninist-Maoist-Fanonist, Jackson rightfully pinpoints the origins of fascism in capitalism. At its core, fascism is a type of capitalist reform, “the rearrangement, the strengthening, and reforming of laissez-faire competitive capitalism.” It emerges “out of weakness in the preexisting economic arrangement and in the old left,” in response to the crises engendered by capitalism. Fascism is cross-class in composition, with the petty bourgeoise and most reactionary sectors of the working class for its political “shock troops,” while integrating the economic and political elite, whose support is vital as well. While Jackson acknowledges its psychological aspects, of which racism is a key component, his analysis of fascism hinges on a core social and economic concept: fascism as the corporative state, a capitalist solution to capitalist problems.

Although no Marxist, Paxton’s nuanced exploration of fascism is valuable as well. Like Jackson, he emphasizes the need to understand fascism as a dynamic phenomenon, one that unfolds itself in stages and limits the usefulness of rigid classifications. Nevertheless, Paxton’s tentative definition is worth quoting in full:

“Fascism may be defined as a form of political behavior marked by obsessive preoccupation with community decline, humiliation, or victimhood and by compensatory cults of unity, energy, and purity, in which a mass-based party of committed nationalist militants, working in uneasy but effective collaboration with traditional elites, abandons democratic liberties and pursues with redemptive violence and without ethical or legal restraints goals of internal cleansing and external expansion.”

Far more than a synonym for dictatorship or authoritarianism, fascism is a particular development that must be understood on particular terms.

Having established some conceptual frameworks for understanding fascism, we can proceed to an analysis of the phenomenon in its South African forms.

The Rise of Fascism among the Volk: The Shirt Movements and Anti-Semitism

South Africa’s status as a settler-colony made it a particularly fertile ground for fascist seeds to sprout. The exterminatory logic of settler-colonialism-wherein the colonizer is driven not only to conquer the colonized people, but expel and replace them on their land- lends itself well to fascism. Unlike settler enterprises like the United States, Canada, and Australia, where disease and genocidal violence enabled the colonizing population to largely wipe out indigenous people, or Israel, where mass immigration and forced displacement resulted in a relative demographic parity between colonized and colonizing people, whites in South Africa were long a ruling minority, empowered by colonialist and imperialist structures but demographically insecure, not unlike the white settlers in British Kenya or the pied noirs in Algeria.

Unable and unwilling to wipe out indigenous Southern Africans, but intent on directly dominating them and their land, white settlers (and particularly the Boers, as heirs to an authoritarian, pseudo-democratic political tradition) were already disposed to the fascist obsessions with false victimhood and violence, especially as Africans and others made economic gains. Though it would be false to suggest that South African fascism could develop in full prior to the 20th century, due to the absence of the essentially modern economic, social, and political conditions necessary for its emergence, the growth of militant Afrikaner nationalism before the 1930s can be seen as a proto-fascism, a new expression of the tendencies produced by and within a settler-colonial environment.

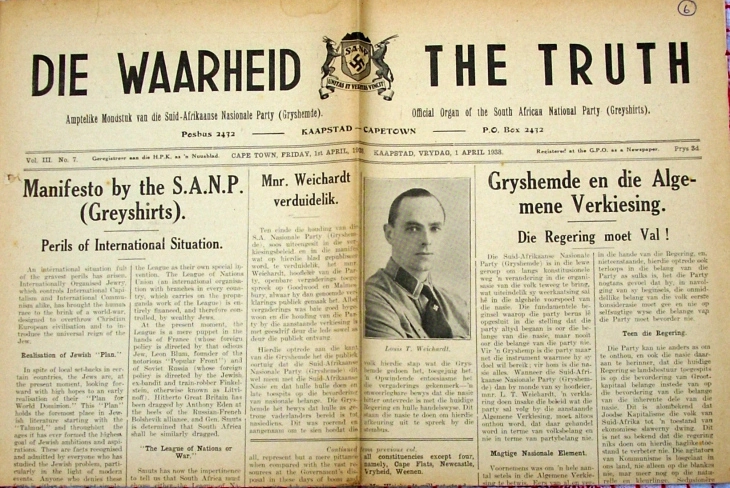

This latent fascism began to manifest outwardly in the 1930s with the rise of the Afrikaner shirt movements. Like their counterparts elsewhere, the South African shirt groups were largely comprised of poor and working-class young men who rejected the niceties of bourgeois, parliamentary politics and embraced a violent, pugilistic style. The Greyshirts, founded by Louis T. Weichardt in 1933, was the largest and most important of these groups, but there were smaller imitators such as Johannes Von Moltke’s South African Fascists.

Notably, anti-Semitism, not anti-Blackness, was the primary racialized organizing principle of the shirt movements. Unlike anti-black sentiment, which nearly all whites in South Africa subscribed to regardless of their other political leanings, anti-Semitism was not a universally held white opinion. According to Patrick Furlong, there was little marked anti-Semitism in nineteenth century South Africa, due in part to the Anglo-German and middle class origins of most Jewish immigrants, as well as the perception among many rural Boers that Jews were a fellow Chosen People. This began to change drastically in the wake of the Anglo-Boer war, as more Eastern European Jews, poorer and more culturally distinct than the earlier immigrants (and more likely to be seen as alien competitors) began to settle in the Cape Colony and Transvaal. In response to the rising tide of xenophobia, the Union governments, including those headed by Smut’s South African Party and Hertzog’s Nationalists, introduced increasingly restrictive and anti-Jewish immigration controls, climaxing in the Immigration Quota Bill of 1929, introduced by then interior minister Daniel Malan, who had earlier trafficked in anti-Semitic cartoons as editor of Die Burger, the National Party newspaper. Jewish South Africans organized fierce resistance against these measures, both legal and extra-legal, but they were not always successful.

The anti-Semitic Grayshirts and similar organizations were therefore working in ideological fields that had already begun to be tilled. However, their brand of anti-Jewish bigotry was a class apart from earlier forms of South African anti-Semitism, Whereas anti-Semitism in South Africa had been discernible previously in literature, cartoons, stereotypes, and social and professional impediments,” this new anti-Semitism was more violent and brazen, and consciously modeled on the grim example set by Hitler and the Nazis. The Grayshirts themselves aped the Nazi storm troopers, with clandestine material and political support from the Third Reich and its operatives in Africa, who considered the Union of South Africa the weak link in the chain of the British Empire, and could draw upon a historical reserve of pro-German sentiment in South Africa.

“Hitler’s triumph, Nazi savagery, and the Nordic myth struck a responsive chord in Afrikaner racists,” Jack and Ray Simons write. Organizing among white workers, farmers, and youth, and wielding the tantalizing “revolutionary” appeals fascism always sports out of power, the Grayshirts and like-minded groups found receptive audiences for their anti-Semitic screeds. Jews could be depicted as both parasitic capitalists, allied with the hated British imperialists, and alien workers competing for Afrikaner/white jobs. Though the South African economy rebounded somewhat quickly after the onset of the Depression, this rhetoric had teeth among many poor whites, who had failed to see much substantive gain from Hertzog’s first government. Furlong notes that “by late 1934, the shirt movements had created an atmosphere of hysteria against Jews…in Johannesburg the streets were filled with anti-Semitic posters in Afrikaans bearing the swastika.” In Cape Town, similar posters accused Jews and Africans of assaulting white girls, melding the threat of two racial enemies together.

The Grayshirts never numbered more than the low thousands, peaking before World War II, but their symbiotic relationship with the much larger National Party extended the reach of their ideology, and represented part of the matrix by which fascism (specifically in its Nazi form) entered the mainstream of Afrikaner nationalism.

The National Party and the Incorporation of Fascism

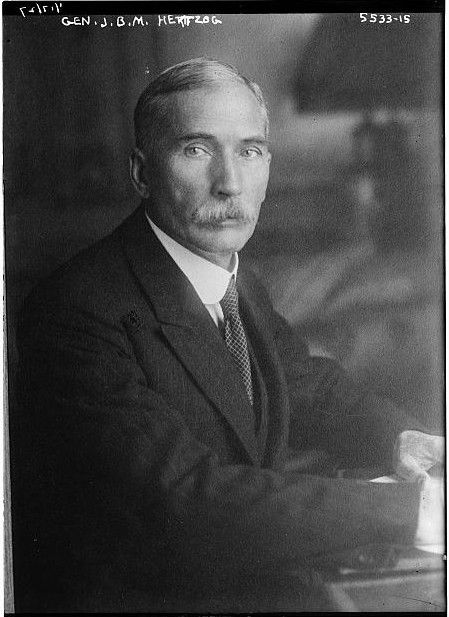

The Nationalists did not begin life as a fascistic organization. Founded in 1914 by Boer general J.B.M. Hertzog, the National Party soon became “a political home for those who felt that the Afrikaners, the descendants of the original white settlers, had become overshadowed in their own land. ” Opposed to the establishment of British capital, English-speakers and the Afrikaners seen as their accomplices, the Nationalists served as the voice of the populist right in white South African politics. When Hertzog and his party came into government with the white Labour Party (an outstanding example of racist settler socialism) the hopes for the Afrikaner nationalist movement were high. Indeed, the flurry of reforms Hertzog passed bolstered the strength of a distinct Afrikaner South African identity, and provided many jobs for poor whites, albeit at the expense of urbanizing African workers .

By the time of his landslide victory in 1929, however, Hertzog had become more accommodating to the old establishment, represented by Jan Smuts and his South African Party. A significant percentage of whites saw little economic benefit from Nationalist policy, and it seemed that the leader of Afrikaner nationalism had forgotten his base, a perception boosted by Hertzog’s coalition agreement, and later fusion, with Smuts in the United Party. This opened up a wide window for even more right-wing forces – the shirt movements and the “Purified” Nationalists of future prime minister Daniel Malan, uncompromising in their dedication to “the volk” – to enter the stage.

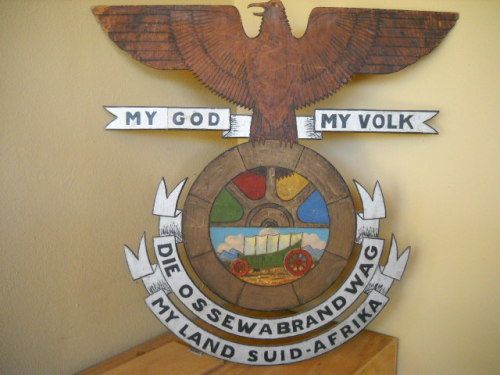

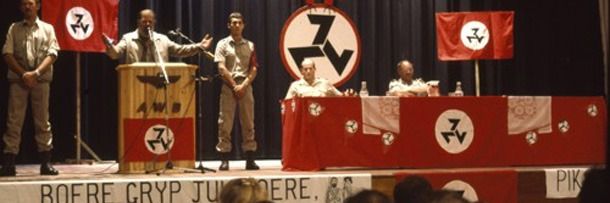

Malan’s wing represented the most radical elements of the National Party, only a step or two removed from the Nazism of the Greyshirts. Like fascists in their “out of power” stage, the Malantites had a militant anti-capitalist appeal, which was on par with the protection of Afrikaner identity. Based largely among whites in small towns and rural parts of the Cape, they saw capitalism, or at least large scale, modern capitalism, as a creature of the British and Jewish oligarchy, the system of the geldmag (the money-power) and the imperialist. Of course, the Malanites’ brand of anti-capitalism quickly melted away once they actually achieved state power. It was this branch of the Nationalists that exhibited the most sympathy towards the Greyshirts and other shirt groups, providing them with favorable media coverage and organizational, financial and political cooperation. Outraged by Hertzog’s pact with Smuts (and by extension, the hated geldmag and British imperialists), he and other hardline dissidents split from the party in 1934, forming the so-called Purified National Party. As the popularity of the openly fascist and pro-Nazi shirt groups waned, especially in the wake of Axis defeats, the Purified Nationalists, bolstered by the paramilitary Ossewabrandwag movement, became a haven for the Afrikaners most inclined towards fascism, and the primary vehicle for white, right-wing opposition to the United government.

South Africa could hardly escape the tumult of the 1930s, which shook the liberal capitalist order to its core across much of the world, but the threats to its establishment were not existential. The Communist Party and other revolutionary socialist organizations were militant, but lacked the mass membership to be a credible threat. The African liberation movement showed signs of strength, but nothing like it would exist during apartheid. Perhaps most importantly, the state and South African/British in South Africa capital was able to more or less weather the economic impact of the Great Depression without a radical overhaul of the system. In other words, fascism was not a necessary step for the South African ruling classes. The lasting effect of the South African radical right, therefore, can found not in the transformation of the South African state or economy along fascist lines, but rather in the complex relationship between the National Party, as the central political vehicle for Afrikaner nationalism, and the fascist movements.

The relationship between the Nationalists and the radical right was a dialectical one, rife with contradictions. As Furlong puts it,

“...for every protestation of democratic values, for every rejection of dictatorship…there was a National Party move in the opposite direction, towards accommodating radical sentiment.”

The contradictions between the fascist movements and the Nationalists proved to be non-antagonistic. They shared common interests – namely, the assertion and construction of an Afrikaner nationalist regime – and what differences they had could be resolved without violence. Therefore, we can see the fusion of the National Party and the radical right during the forties as both a loss and a victory for both parties. The Nationalists were simultaneously captured by the fascist movements and their captors, able to outmaneuver them as an independent political force but irrevocably influenced by them. The organization that emerged from this synthesis was quite different than either of its components, neither truly fascist nor democratic, but a vehicle for a curious and distinctly South African blend of authoritarianism.

Why does this matter? Why should communists today care about the role of fascism in pre-apartheid South Africa, especially those far removed from it in time and space?

First, it illustrates the importance of understanding fascism for what it is and can be, not what we wish it to be. We live in a dangerous age, where the cataclysmic tendencies of capitalism threaten to devour the planet and the human race alive, but revolutionary movements are not yet strong enough to seize power and reverse the tide. Fascism is on the rise everywhere we look, helped by the failures and cowardice of liberals, and ready to combine its forces. But these threats, despite certain historical similarities, are not the same as those earlier generations faced. We must understand that modern fascism is not the Third Reich, Mussolini’s Italy, or another “classic” fascist regime dressed in 21st century clothes. It does not and will not look the same wherever it rears its head, and we can’t beat it with the exact same strategies and tactics our predecessors used. We cannot underestimate how flexible it can be, how it can co-exist alongside the trappings of democracy. To defeat fascism and build socialism, we must understand history not as a blueprint, but as a guide.

The history of South Africa has a double importance for white communists in Amerika and other colonial countries. As Aimé Césaire and other anti-colonial thinkers past and present have taught us, there is a direct relationship between fascism and colonialism. In monstrosities such as the United States, built on stolen land, stolen labor, and countless corpses, a kind of immature fascism has always been a fact of life for just about anyone who doesn’t fit in the “white man’s country.”

Most whites, fattened by the fruits of genocide and mass theft, have been content to keep this status quo afloat, at least as long as it didn’t threaten them materially. They have never represented the vanguard of revolutionary consciousness or action. Many white radicals, including those who call themselves anti-racist, anti-fascist, and even anti-colonialist, still can’t deal with this reality seriously, and fail to recognize the stupidity and recklessness of waging struggle without the leadership and mass participation of revolutionary Black and African, Latino/Latina, Indigenous, and Asian people. This was as true in 20th century South Africa as it is for us today. A revolutionary movement that is not grounded in the experiences and leadership of oppressed people, that coddles whiteness instead of burying it, is doomed to fail. And we cannot afford to fail.

Sources:

Blood in my Eye, by George Jackson.

Class and Colour in South Africa, 1850-1950, by Jack and Ray Simons.

The Anatomy of Fascism, by Robert Paxton.

Between Crown and Swastika, by Patrick J. Furlong.