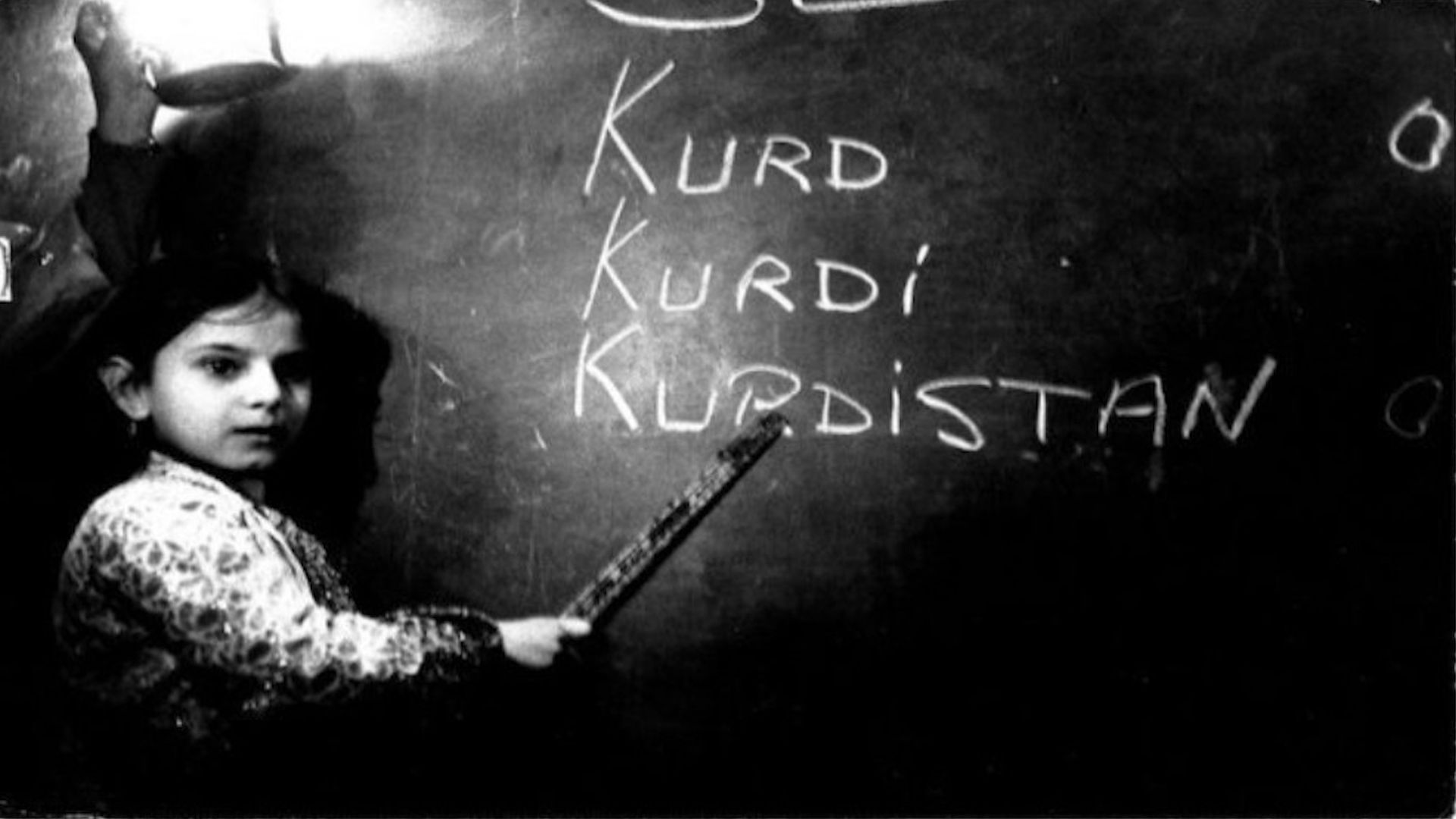

International Mother Language Day 2020: Suppression of Kurdish by Turkey

"As Apê Musa remembers, 'If my language is shaking the foundations of your state, it probably means you built your state on my land.'"

Friday, February 21st 2020, International Mother Language Day was celebrated across the globe and amongst many Kurdish people who celebrated their own native language and its almost innumerable dialects, both across the geo-cultural region of Kurdistan and amongst the Kurdish diaspora. Therefore an appropriate examination of the recent history, of suppression, of the people’s Kurdish mother tongue, within Turkey can be held to mark such an international celebration.

The suppression of the Kurdish language has varied from state to state and era to era. As one of the world's oldest Indo-European languages, and one with many subdivisions such as Zaza, which has a majority in some areas of North-Western Kurdistan, all rich in history, culture, and socio-linguistic importance.

However, for an analysis surrounding the current atmosphere, it’s mostly appropriate to study starting from the emergence of the Turkish nation-state following the collapse and dissolution of the Ottoman empire in the 1920s.

The power vacuum of its dissolution was quickly filled-in with Turkish nationalist organisations that ultimately formed the Turkish Republic in 1922 under its first Prime Minister and President, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk. Revered in a cult of personality among Turkish nationals since the inception of the Turkish nation-state, he was adorned the honorific name "Ataturk" (literally ‘father of Turks’, a title even adopted by the former dictator of Turkmenistan where it was altered for his own respective ethnicity).

However, to the ethnic minorities living on and beyond the borders of the Republic of Turkey, Ataturk is seen as a genocidal, tyrannical figure. He is attributed to numerous massacres’ against ethnic minorities such as the Istanbul Pogrom (as part of the wider campaign of genocide against Armenians and Pontic Greeks) and the Zilan Massacre against ethnic Kurds. These were attributed to be a part of his program of ‘Turkification’ – the creation of an ethnically homogeneous Turkish state, which he attempted to forge through mass genocide and forced assimilation. Another part of this program was the criminalization of the Kurdish language in 1938, another act of forced assimilation. Where military force failed, the repressive state apparatus would prevail; as such, Ataturk targeted a cultural pillar of a people: their language.

The oppression of the Kurdish language and the forced usage of the Turkish language in schools led to a drastic decrease in the literacy of Kurdish regions and the adoption of Turkish vernacular into what became holes in the knowledge of the Kurdish language among many villages. Kurds who learned Kurdish as their mother tongue would often go to Turkish schools to be confronted with a language absent at home (Aydin & Ozfidan, 2014: pp 21-48). The linguistic assimilation campaign was not only limited to schools but also in private life, public areas, and Kurdish publications, and while the Turkish constitution of 1961 permitted the publication of Kurdish works, individual Kurdish writings were quickly banned as soon as they were published. In private life, Kurdish households had to use satellites to access Kurdish TV outlets that were stationed in other countries, leading them to being stigmatized in Turksih neighborhoods for the satellite receivers that decorated the sides of their houses; everyone knew what they were for, and people refused to acknowledge the existence of Kurds, so they harassed them – simply for existing.

The 1980 Coup and its military junta government would only intensify the state repression, claiming fidelity to Ataturk's ideals. During the rule of the junta, the constitution would be modified in 1980 to establish Turkish as the only language of the state:

“Training and education shall be conducted along the lines of the principles and reforms of Ataturk... under the supervision and control of the State... No language other than Turkish shall be taught as mother tongue to Turkish citizens at any institutions of training or education.”

And in the following civilian government (1983 to 1991), Kurdish songs were strictly forbidden, resulting in a black market for pirated Kurdish music. Broadcasts and publications of languages other than Turkish were also banned.

In 1991, Kurdish was legally decriminalized. Still, this was a case that was purely penned in legal stature and was not, in fact, the true reality of the situation; Kurdish was permitted only in private. Permits for public Kurdish celebrations were almost always denied, as usual. A Kurdish Parliamentarian, Leyla Zana, was imprisoned in 1991 for speaking Kurdish during her oath to Parliament. Similar cases include, in 2007, the detaining of the former MP Osman Baydemir for using language that the Police argued breached the constitution for its use of the letter ‘W’, which is not in the Turkish alphabet, and, in 2017, was forced into exile for also mentioning the word "Kurdistan" in the Turkish Parliament – an illegal act.

While Kurdish, as a subject of study, was permitted in the national curriculum for Universities since 2009 (and all other schools since 2012), many schools are still denied the opportunity to teach it under minor bureaucratic justifications such as the size of a classroom's door. Thus very few schools in Turkey actually teach Kurdish (a peak of three in 2014) and it may only be an individual subject (it is illegal to have purely Kurdish schools or even use the language in any other manner than as an educational tool). So, progress in education was, as were all other aspects of society, very limited.

In the realm of the media, the 1991 legalization of Kurdish soon allowed for the first legally-released Kurdish film in Turkey; twelve years prior, the film's director, Nîzamettîn Arîç, was arrested for singing in Kurdish at a concert in Ağrı. In 2006 the Turkish government also permitted the limited use of Kurdish in select private television channels on the condition they were not to be used in an educational manner or in the format of a children's cartoon. This would be later relaxed, but in 2015, following a failed coup attempt, the President would garner emergency powers and decreed an executive act that outlawed all Kurdish television once again, alongside scores of Kurdish institutions, media organisations, and the remaining language schools.

The Turkish Constitution of 1980 keeps Turkish as the official language of the state.

These legislations were not based on some sort of merciful, benevolent, or kind-hearted government, but were instead compromises made in reaction to the masses of Kurdish people rising up in an act of Serhildan (‘Resistance’). This form of protest, involving boycotts and direct action, began in 1990 and resulted in the aforementioned empty-handed 1991 decriminalization of Kurdish.

Due to the aforementioned 2015 state of emergency, almost all the prior limited-progress of legalization regarding the Kurdish language had been reversed with a Presidential purge of Kurdish language associations, schools, public officials, legislators, and media organisations. One victim of the purge was the 25-year-old Kurdish Institute in Istanbul which, as reported by The Nation, was

“The institute [that] became the foremost promoter of Kurdish-language education and standardization during a period of intense and violent repression of the Kurdish minority.”

More than 100,000 appeals have been issued by a plethora of Kurdish institutions, but as the seven commissions they were all sent to were filled with government supporters, little progress can be expected.

Plenty of individual cases have emerged since, such as the ban on the HDP party’s Kurdish campaign song for the Turkish 2017 referendum, "Bejin Na" (‘Say No’); the courts stated it had violated the linguistic ‘wholeness’ of the Turkish homeland, citing articles of the 1980 Constitution. The Kurdish mother tongue and its education are currently, and has been constantly, under threat by the Turkish nation-state and its programme of Turkification. Despite this, as Sami Tan, a member of the Istanbul Institute, states, “The Kurdish language has overcome so many obstacles. It will overcome these times, too.”

According to a source in Rudaw, a Kurdish mother in Turkey stated that

“[My children] were speaking in Kurdish until they turned to five. As soon as one started school, he was cut from the Kurdish language. His friends and teachers are all Turks. Sometimes when I would ask them in Kurdish, they would answer in Turkish. If they had studied in Kurdish, they would not have forgotten Kurdish,”

The mother tongue of many Kurds is fading as forced assimilation continues. International Mother Language Day becomes an important reminder for the Kurdish people to retain their cultural heritage and to defend it, by any means necessary, from the Turkish state's encroachment. There needs to be a lobby by all UN states on the basis of the 2007 UN General Assembly Resolution, "to promote the preservation and protection of all languages used by peoples of the world" – Turkey is no exception.

In the following International Mother Language Day, and subsequent annual celebrations such as Kurdish Language Day (celebrated annually on May 15th) there must be a remembrance of the sacrifice and hardships endured by the Kurdish people for the perseverance of their mother tongue and its penultimate victory to come. The day is once again important for all Kurds who must continue the struggle for representation of their mother tongue in all sectors of society. As Apê Musa remembers, "If my language is shaking the foundations of your state, it probably means you built your state on my land."

Roja zimanê dayîkî pîroz be!

Happy international mother language day!