Dragging White Leftists: My Anti-Drug

"Today, if you are in good faith, you should do like Sartre did with Fanon and ask what, in spite of all, you can learn from our voices, now that we no longer address ourselves to you, but rather, to one another about you and beyond you."

Part One: The Opening Salvo

As a broke Black commie theorist living in the financial center of racist, capitalist AmeriKKKa, there are very few reliable sources of pleasure in my daily life. Jobs are hard to come by, even with a college degree, the rent is higher than I could reasonably afford at a $15 minimum wage, and the remaining “cost of living is preposterous,” to quote the great poet Yasiin Bey. So, my disposable income is a whimpering joke. Even the “free” distraction of New York’s diverse scenery is clipped by the prohibitive cost of transport. My financial and residential rut is rather underlined than compensated by the regular crop of trendy new cafes and Asian-fusion restaurants that draw white Midwestern yuppies to this rapidly gentrifying section of BK. The vibrant lifeworld shaped by the African workers here in Weeksville is lately threatened by a pestilence of smartly dressed, white twenty-somethings, buzzing around this poorest corner of Crown Heights, since other Pilgrims have already planted flags on the more fashionable frontier of Nostrand and Atlantic. The askari units of Black and Brown police help them feel safer in these pioneering efforts, even while threatening the lives and liberty of those jobless and desperate workers whose collective genius makes Black Brooklyn so alluring to begin with.

My modest weed habit helps me cope with this economic and psychic assault on my Black nation. But even a dub of Sour D is a pricey investment when you’re down and out in neocolonial NYC. Who needs a spliff, though, when instead you could just drag the smug white leftists who remain blissfully unaware in all this?

When the dread down the way can’t be found and my delivery guy is too expensive, I get my dopamine rush from firing up the asses of white leftists instead. For all their sophisticated takes on Lacanian psychoanalysis and surplus-value extraction under neoliberalism; for all their clipboarded enthusiasm for Ocasio-Cortez and Salazar, spilling over the pretty walls of the Pratt Institute into the train stops of Bushwick, the white left in New York – as everywhere else in the United States – still blinks uncomprehendingly at the banal, yet fundamental facts of settler-colonialism and national oppression, the prosaic truths that explain Black workers’ powerlessness far better than could a dozen volumes of Zizek or David Harvey.

Now, I wanna stress that I do have fun with the shit. It doesn’t stop me from organizing the masses of my people, whose record of revolt against capital in countless cities throughout the 20th century reveals their great revolutionary potential despite the consent (better: collaboration) of the white majority. So when I drag y’all like this, don’t get it twisted for bitterness over failure: there’s more of Nietzsche than Schopenhauer in my mockery of white radicalism. To paraphrase Fanon, the time is long gone when I'mma go hoarse from bitterly shouting at white folks, what has been better said by past poets of rage. And I say this because people sometimes tell me that I scapegoat white folks, especially white leftists, for the failed AmeriKKKan revolution, when “we” should instead be consolidating our forces in the struggle against Trumpism and neoliberalism. Everybody who says those kinds of things about Black revolutionary nationalists like myself should know that anything we say and far worse can be found in the music and folklore and written word of Black so-called Americans who lived almost 100 years ago, that is, half a century from Emancipation; and that when there is any bile in our voices today, it’s because, for generations, our great cry failed to find an audience with all sectors of white public opinion, reactionary or “radical”.

Lately though, in fact, white radicals have noticed that a distinct Black radical tradition does exist... but only to more carefully indemnify themselves against it. The phenomenon of tokenism is nothing new; and to appear more truly universal, First World Marxists have lately taken to retroactively tokenizing Black radical figures who rejected that status their whole long lives.

But maybe they should go back and really read WEB Du Bois, for example, instead of just noting with self-satisfaction that late in life he joined the CPUSA and penned a paean to Stalin. They should use their material privilege to pore over the thousands of pages that Du Bois devoted to the critique of Western civilization, of the white left, even of white aesthetics. His undergraduate commencement address at Harvard was about the arch-defender of slavery, Jefferson Davis, as dubious representative of American (white male) civilization. He wrote a whole novel about the rising peoples of the Third World, called Dark Princess, in which Afro-Asian humanity eclipses this decadent white world; that is largely the theme, too, of his first two autobiographies (Darkwater and Dusk of Dawn). His greatest work, Black Reconstruction, casts off several classical Marxist assumptions about the real sources of progress in modern life: from the reactionary character of pre-industrial labor, to the deracination of the white worker’s consciousness, his organic solidarity with the oppressed and antagonism to (white) capital. In landmark essays like “The African Roots of War” and “Marxism and the Negro Problem,” Du Bois identified long-neglected, racial-ideological sources of radicalism and reaction in African and white workers, respectively; springs of class activity that, under classical-Marxist assumptions, could only be called epiphenomenal (i.e., caused by economic, substructural forces, without in turn having any determining effect upon the economic base). And while he’s often remembered mainly as an integrationist, Du Bois died in exile from the US and its deathly-white culture, a proud citizen and resident of Ghana. (To say nothing of his jabs at white people's ways, and even their physical features, in such overlooked essays as "The White World" and "The Souls of White Folk" – he was not y'all's fan like that.)

Richard Wright is another one who needs less hollow celebration and more study. Probably most major AmeriKKKan school systems have featured one of Wright’s texts in their curricula at one point or another. But have y’all ever seriously read the preface to Native Son? Here Wright talks about how Negroes in large sections of Chicago's Southside initially identified with Hitler in the great war, just because of the hell they were catching from the AmeriKKKan mainstream. It’s a frightening text, for more reasons than the white psyche is prepared to acknowledge. According to his account in “How Bigger Was Born,” part of that classic work's political motivation was to explain why the sub-proletarian Black male was disaffected both from Northern mainstream society and the Communist Party; why he was drawn instead toward Garveyism or to nihilistic violence. (A concern, by the way, that is carried over into the treatment of “the Brotherhood” in Invisible Man, for all of Wright’s aesthetic and political differences with Ralph Ellison.) And this is in spite of the pseudo-nationalist commitment of the historical CPUSA (which finds a miserable echo in several smaller, integrated Marxist formations in our major cities today).

The Black Power movement’s most Socratic figure, Harold Cruse, is criminally neglected by the millennial left; but he gives a clue to the alienation of Wright’s subjects in his mammoth study, The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual. The program of the CPUSA (originally: Workers Party), though featuring an ambiguous plank on Negro self-determination in the Southern Black Belt, had only very reluctantly adopted this position, and had advanced it in very clumsy and contradictory ways before finally rejecting it under Earl Browder’s tenure. But that is because that plank did not originate with the US Communist movement’s leading thinkers, but with Claude McKay and Sen Katayama, who at the Fourth Comintern Congress went to Karl Radek over the heads of the integration-minded whites and Negroes of the US delegation to (correctly) frame the US Black struggle as a national problem. This intervention reflected their awareness of the great appeal of Garveyism with the masses of Black working-class people; and it originated in the African Blood Brotherhood's attempted synthesis of those basic nationalist impulses with class radicalism (Cruse: 44-45, 54-57). In today’s “multinational” formations, much is said in celebration of Black Communists in the historical Party, like Harry Haywood, Claudia Jones, and Queen Mother Moore. Terribly little, if anything, is said about the real source of their abortive struggle in the Party against the “Browderist” integrationist line, which had far deeper social roots than millennial Marxists know or care to admit – in that party's predominantly white-settler and petty-bourgeois leadership and rank-and-file.

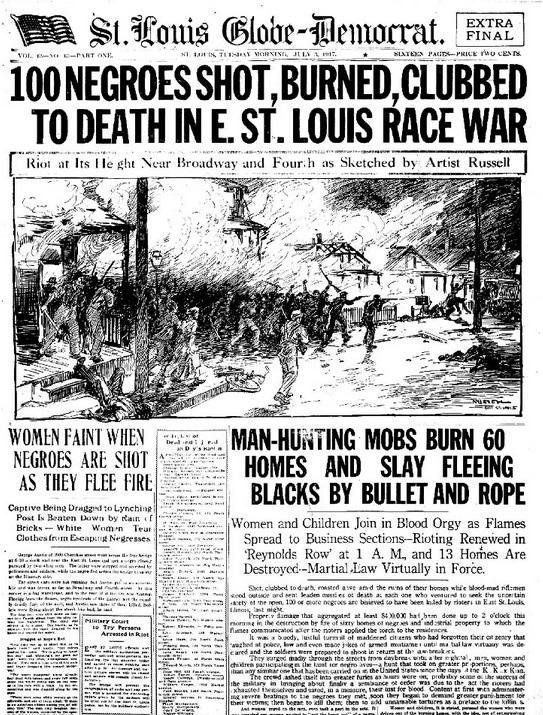

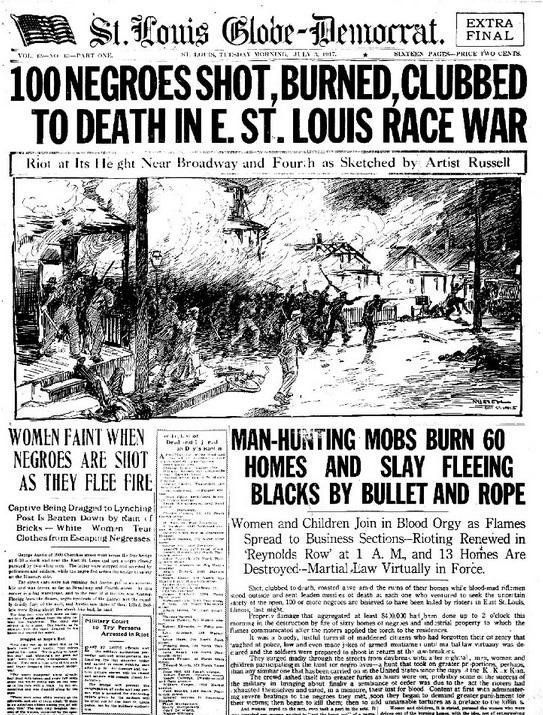

Black radicals were impatient for dramatic revision of Marxist assumptions about the relationship of race to class over a hundred years ago – when most of us couldn't look white folks in the eyes without life-changing/ending consequences, when we had little chance of success in collective self-defense. We sat back dumbfounded, while your beloved white workers massacred our people in Detroit, Chicago, East St. Louis, and Springfield, Illinois; and our amazement hardened into contempt for the “rising tide” that would lift all boats in the very white visions of Eugene Debs, Norman Thomas, and Earl Browder. We learned (terribly slowly) to applaud Mr. Garvey’s foresight in flouting the politics of (lily-white) trade-unionism and integrated-party radicalism, even while we transcended the limits of bourgeois nationalism toward our own, self-determining varieties of proletarian militancy in all-Black formations such as the League of Revolutionary Black Workers. Long ago we have concluded that y'all just do not want to listen to our screams, and have traded them in for the ironic laughter of our signifying fore-parents in Southern fields.

Or, if you do have ears to hear, but simply lack the time and resources to learn these things on your own, then you hardly suspect that the institutions you have trusted as the flower of civilization have (clumsily, or cowardly) failed to also bring you truth when teaching you how a bill becomes a law; or how your daddy's manicured lawn and income tax, your clean neighborhood and municipal park, all hang together in a great democratic plan. Meanwhile there have been more Black people killed by police this past year than during any year of lynching, and there are more Black people in jail today than were in chains during slavery, and there are more of us unemployed than during the hot '67 summer.

Today, if you are in good faith, you should do like Sartre did with Fanon and ask what, in spite of all, you can learn from our voices, now that we no longer address ourselves to you, but rather, to one another about you and beyond you. Consider this series of articles a (somewhat indifferently built) bridge in your education. If you are in good faith about wanting to learn more about who you really are, and not seeking validation of what you think you are.