Community Control of the Police: Is It Neocolonialism?

"Black people can not have “power” over the police because under colonization Black people have no power. Insofar as power entails the ability to overdetermine and shape the culture of policing, power will always be reserved for the colonial policing state."

Where the watershed trial and conviction of Derek Chauvin in the murder of George Floyd has made abolishing the police that much more difficult, proposals for community control struggle to set the agenda for the movement to come. The Community Control of Police position (CCOP) generally envisions that Black communities will be able to control the police through a civilian control board. One vision in particular, argued by Max Rameau in his position paper “Community Control over Police: A Proposition,” maintains that current police departments can be voted out through a local ballot initiative and be replaced with new police departments under the control of the community.

For Rameau and many advocates, the central issue of police violence is power, and consequently, their arguments for community control stem from the assumption that “who” controls the police will determine police behavior and social function. Curiously, many advocates also locate their vision of CCOP within an anti-colonial analysis. Rameau himself states several times throughout his position paper that Black communities constitute a domestic colony in the US and that the police constitute an occupying force. This is curious indeed because as I will demonstrate, community control of the police not only remains inconsistent with that premise, but its proposals for practical application actually amount to neocolonialism.

To be sure, there is no shortage of Black individuals who can “control” the police, or at the very least exert some sort of executive influence on police departments. According to an article from Insider, there are an estimated 21 Black police chiefs operating in America’s 50 biggest cities. Out of that number, Minneapolis police chief Medaria Arradondo became the first and only Black police chief to ever testify against a police officer in court for a high profile, police-involved murder. More than a third of America's top 100 cities are governed by Black mayors. Lori Lightfoot of Chicago, Muriel Bowser of D.C, Stephanie Rawlings-Blake of Baltimore, and Keisha Lance Bottoms of Atlanta all retained some control over police, and were in office during a time of high profile police-involved violence in their respective cities.

Black administrators in these positions have not been able to lower police violence, nor ensure just outcomes for the victims of police violence, and more often than not have colluded with the police. Their salaries are financed by city and state tax dollars, their class interests align with the protection of property relations, and their jobs are beholden to the white supremacist power structure. But more than anything else, these Black administrators (however well intentioned) have failed at changing the police because “who” controls the police has never determined the function of the police or of policing.

Robert Allen, author of Black Awakening in Capitalist America, would have defined the machinations of these Black administrators as an expression of neocolonialism. In his seminal text Allen described the Black population in America as an internal colony, forming the basis of the internal colony theory that Rameau and company are working from. Allen argues that the Black community experiences subjugation, exploitation, and occupation in the same ways a third-world colony experiences colonialism from a foreign imperialist power. However, the crux of Allen’s argument, written at the tail end of the 1960’s, asserted that the colonial relationship between the internal colony and the state was in a transitional phase. The era of Jim Crow segregation, which had receded into history by the end of the 1960s, was more analogous with classical colonialism. Much like the former colonies within the third world, the Black internal colony was undergoing a transition into neocolonialism:

“To be more explicit, it is the central thesis of this study that black America is now being transformed from a colonial nation into a neocolonial nation; a nation nonetheless subject to the will and domination of white America. In other words, black America is undergoing a process akin to that experienced by many colonial countries.” (Allen, 11)

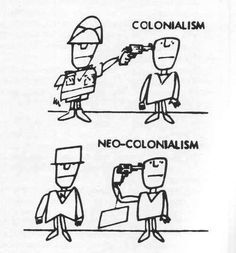

Neocolonialism is the process in which indirect rulership is established in a former colony through the use of economic domination, market influences, and the use of proxies made up of the colonized leadership. Allen uses the example of Ghana, which was placed back under the thumb of the British after it won its independence, in part due to the acceptance of economic aid and the establishment of a political elite willing to play proxy to the interests of finance capital:

“Under neocolonialism an emerging country is granted formal political independence but in fact it remains a victim of an indirect and subtle form of domination by political, economic, social, or military means. Economic domination usually is the most important factor, and from it flow in a logical sequence other forms of control.” (Allen, 14)

Of course Ghana, like most African countries undergoing decolonization, retained a police force left from the vestiges of British colonialism; a police force which came fully under the control of Black Ghanaians. We will return here to policing on the African continent for its wealth of case studies in which Black people control the police and still experience all of the problems inherent to policing.

Allen goes on to analyze the American context, where the forces of internal neocolonialism manifest in the emergence of corporate interest in a Black middle-class:

“They endorsed the new black elite as their tacit agents in the black community, and black self determination has come to mean control of the black community by a "native" elite which is beholden to the white power structure.” (Allen, 19)

In his analysis of the Ford Foundation and other corporate interests in activism, Allen was identifying the early formations of the non-profit industrial complex. Through the help of proxies in the Black community, grassroots organizing was cornered into becoming increasingly co-optable and financially dependent on the private sector. This came as more Black people ascended to positions of political power and influence. The new Black political elite became junior partners who acted as go-betweens for the US settler colonial state and facilitated indirect rulership, much like their African national bourgeoisie counterparts, by sequestering radicalism among the Black masses and maintaining close economic ties with the white power structure.

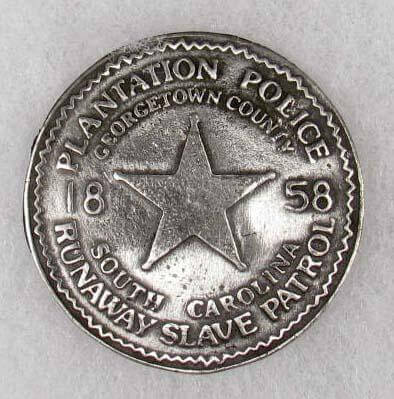

However, the program of neocolonialism need not only involve the activities of the Black bourgeoisie. Interestingly enough, Allen was writing during a time when more Black people were becoming police officers and more Black faces were incorporated into the policing apparatus. This mirrored the headmen system, a centuries old technique used by white masters during slavery to police Black activity on the plantation through the appointment of Black overseers. Black people policing themselves became a crucial part of the maintenance of the slaveocracy, as the Black overseer ensured the surveillance and obedience of the enslaved with minimal direct supervision from the white slave master.

Similarly, the wave of Black people entering the police force towards the end of the 1960’s, through the ruse that more representation would equate to better police practices, fit comfortably with the program of indirect rule mounted by the state and the colonizer elite. The series of riots that occurred during the 60’s in addition to the growing revolutionary militancy and anti-cop feeling within Black neighborhoods made direct occupation by white police officers more expensive and less ideal. This came as white flight from the inner-city facilitated an increase in poverty, unemployment, crime, and drug abuse in Black neighborhoods. If the state’s approach to governance was transitioning to neocolonialism with regard to its Black population, its methods of policing would also have to change. The heavy-handed police response to Black insurrection was coupled with the emergence of the Black police officer as one answer to the problems of overt direct occupation.

That neocolonialism was crucial to Allen’s formulation of internal colony theory is important here because it highlights that Allen was not just arguing that Black people are an internal colony, but that the colonial relationship was changing.

Max Rameau, in his position paper and in other writings, simplifies the colonial analogy while failing to account for Allen’s more nuanced account of neocolonialism:

“In form and in function, Black communities are a domestic colony inside of the United States. If Black communities are a domestic colony, then that colonial relationship of exploitation and oppression is enforced by an occupying force: the police.”

Nowhere in his theory of internal colonialism did Robert Allen ever endorse community control of the police. Yet this failure to account for the nuances in Allen’s argument lends itself to Rameau’s inability or refusal to see his proposals for community control as the logical extension of a neocolonial project, brilliantly repackaged as a bid for dual power, all the while remaining economically and institutionally beholden to the very white power structure it claims to be against. It accelerates the headmen system to its logical conclusion, developing Black communities where residents randomly engage in the administration of newly developed police departments, where mobilization energies are spent investing in police work, and where the abolition of the police is promised but never comes.

Let's take a moment to examine the details of Rameau’s proposals in full. His premises again maintain that the question of policing is a question of power. But contrary to the great many anti-colonial thinkers who understood colonialism as a question of armed struggle, Rameau seems to think it is a question of democratic power:

“In the face of protests against police brutality and abuse, the real question, then, is not about community relations, civilian oversight, appropriate levels of training, or even well intentioned slogans. The core issue is one of democratic power.”

It is important to note that colonial occupation is not secured by democracy, it is secured by violence. The colonial regime, as anti-colonial theorist Frantz Fanon reminds us, is here through the force of the bayonet. Rameau argues that Black people have never had a chance to consent to occupation, which he identifies as necessary for democracy:

“By definition, however, no people grant consent to colonization or occupation. In practice, Black people in American have never been afforded the opportunity to grant consent to an armed force empowered to stop, detain, arrest and even take the life of members of our community.”

But if Black people have never been afforded the opportunity to consent, it is because colonization necessarily involves the usurpation of consent. It is actually constituted by domination which is the opposite of consent. No kind of democratic process can secure a colonized people's right to vote whether or not they will be dominated, simply because the colonial regime will never allow it. Wherever possible the colonizing power will use force to usurp the will of the people, and where it is adverse to using force, it will use the preferred soft power associated with neocolonialism.

Case in point, let us return to Ghana. Ghana, like many African countries, obtained its independence through a non-violent referendum. The Convention Peoples Party (CPP) organized a non-violent mobilization campaign that eventually succeeded in exacting a referendum that brought the colonial territories of the Gold Coast under the British Commonwealth of Nations via the Ghana Independence Act 1957. Of course, membership in the Commonwealth involved the continued economic relationship with Great Britain. The granting of so-called independence became the answer as Britain sought to jettison its colonial holdings after being severely weakened by WWII, while also struggling to maintain its influence and economic interests in its former colonies. Ghana, like many other former colonies, entered into debt and economic dependence the second it became independent of Britain. Kwame Nkrumah became the first president of Ghana but was ousted by the neocolonial national bourgeoise in 1966, and Ghana’s transition to neocolonialism was complete.

Referendums were nothing more than a step in the neocolonial process. The colonies who opted to vote out the colonizers instead of entering into armed struggle were the most likely to be reincorporated into a relationship of subjugation and dependency. After his ouster Nkrumah himself regretted the manner in which Ghana had gained independence and turned towards armed struggle as the best way to accomplish African liberation. It is not possible to vote out colonial occupation because once again, colonization is not secured by democracy, it is secured by violence. The same can be said for voting out the police.

Rameau must make the question of policing a question of democratic power because the essential part of his argument is that the police can be voted out of the Black community through a ballot initiative. If he is trying to be clever when he asks the question “so let me get this straight, you are telling me I can vote out the police,” it is because even he has to acknowledge how ridiculous and contradictory this proposal sounds. If the incredulousness of “voting out the police” elicits suspicion from the average reader, it is because it is a fiction and a pipe dream. In practice it is no different than the referendums put forward by the colonies to vote out the colonizer, almost always guaranteeing continuing forms of neocolonial domination if granted by the colonizer at all.

The practical applications of Rameau’s voting scheme raise more concerns. According to him, areas would have to first be sectioned off into policing districts before voting commences. These districts could either adopt the existing policing jurisdictions or invent new jurisdictions. The districts then put the police up to a vote, and each district votes independently on whether their district will keep the police or opt to form their own police department. What remains important for him is that each jurisdiction is economically and socially “contiguous,” which is shorthand for demographically homogeneous:

“These districts can be identical to existing commission districts, wards or other political boundaries, or can be drawn up entirely from scratch. The districts should be physically, economically and socially contiguous, enabling Black communities to have their own policing district or districts.”

Rameau needs to reorganize police districts because as long as voting outcomes are determined by majorities, he needs strong Black demographic majorities in the areas voting out the police or the ballot initiative will fail. What this virtually does is renegotiate and reinforce the red line, since policing would be non uniform between districts: some districts will clearly be more policed than others, making it unclear what happens to a Black person once they step out of their district or live in a district that did not vote out the police. This dependence on demographic majorities produces strongly segregated regions along the lines of economic and racial demographics, which amplifies racial disparities, limiting social mobility and free movement between districts. Predominantly Black areas already experience underfunding and deprioritization as it is. It is unclear what, if anything, renegotiating the lines of policing districts will do to prevent targeted underfunding of predominantly Black districts.

CCOP proposals outlined in Rameau’s position paper rely on rigid notions of racial demographics that assume that Black communities are uniform and stagnant, when they are in constant flux due to the forces of gentrification and development. With Black people comprising 13% of the US population, it is simply not realistic to expect ballot initiatives to result positively for Black people in areas that do not hold Black demographic majorities. Unless Black people are the only ones who get a vote, all this does is give a vote to everyone who lives in the district, including gentrifiers. This is on top of the forces of gentrification, incarceration, and death, which are greatly truncating Black numbers in places with historic Black majorities.

Neocolonialism will have you voluntarily redlining your own community in order to substantiate a ballot process that is unrealistic, in order to vote out colonial occupation, which is unlikely. The reorganizing of policing districts is cop work and reinforces the economic and structural stratification of Black people behind a veneer of anti-colonial politics. Setting up district boundaries that vary in the use and intensity of the police based on a given area further ghettoizes the ghetto.

The end-goal for Rameau’s ballot process is for Black districts to vote out the current police department and replace it with a new police department. He strongly emphasizes that his CCOP plan has no interest in taking over already established police departments:

“To be clear, this vote is not to take control over an existing police department, but to establish a new one. No colony seeks control over the occupying army, they pursue an end to colonialism and realization of self-rule. In this instance, the vote is to establish a Civilian Police Control Board.”

Rameau seems to think that once a new police department is created under the control of a civilian police control board it somehow ceases to be an occupying army. In reality the function of the police remains the same. Policing is that practice of coercive social control, always overdetermined by ruling class interests, in the service of maintaining social hierarchies. It is used to enforce occupation, class differentials, property relations, and the enforcement of ability, gender and sexual categories.

In his own words, Rameau seemingly contradicts himself and his whole project when he states:

“The fundamental function of police in any society is to enforce the will and mores of those in power, whether that will is formally encoded in law or informally ingrained in social custom. Because they are the enforcement wing of the system, any campaign whose primary objective is to convince the police to disobey the will of those in power- to disobey their boss- and, instead, adhere to the wishes of those with no power, is not only illogical, it is doomed to fail.”

Why does Rameau not recognize his own project as illogical and doomed to fail? He might say that forming police departments under the control of Black communities “shifts power” to those Black communities. But as I have demonstrated at the start of this paper, control does not equate to power. Black mayors, city officials, and police chiefs are incapable of changing the police because controlling the police does not equate to power over policing; the superstructure of policing which exceeds formalized police departments, encompassing everything from private security to vigilantism, hospitals to schools, prisons to mental health institutions, to policing at the interpersonal level, are all endemic of a culture of policing engendered by the colonial policing state.

Black people can not have “power” over the police because under colonization Black people have no power. Insofar as power entails the ability to overdetermine and shape the culture of policing, power will always be reserved for the colonial policing state. In the colonial context, policing is grounded in the articulation of criminality by the colonizer, which always hinges on the colonized subject being the perpetual criminal element that enables policing. In the case of Black people we might add that criminality has become a part of the constitution of Blackness under the white supremacist superstructure. Black people have no power to change this criminalization, which calibrates the very reason and usage of policing.

The necessary distinction between power and control is what defines neocolonialism. Neocolonialism is in fact what happens when a colonized people are in "control" but do not have power.

Let us return to policing on the continent of Africa for another example. Policing in Africa has been fraught with corruption and humanitarian abuse. While Black people in the United States rose up to protest the killing of George Floyd, Nigeria was in uproar after a video of a man being murdered by the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) went viral in October of 2020. SARS had become notorious in Nigeria for subjecting Nigerians to extortion, torture, and extrajudicial killing. According to a June 2020 Amnesty International report, SARS was responsible for at least 82 documented cases of torture, ill-treatment and extrajudicial execution between January 2017 and May 2020. SARS abuses disproportionately targeted women, queer, and trans Nigerians.

For all intents and purposes SARS, was controlled by Black Nigerians. The larger Nigerian Police Force (NPF), who is also responsible for similar abuses, is controlled by a Black Nigerian government. Similarly to Ghana, Nigeria won its independence from the British through relatively peaceful means and entered the British Commonwealth of Nations in 1960. By the 1970s, Nigeria was in debt and turned to the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and the World Trade Organization for financial assistance. Nigeria was put through structural adjustment programs and austerity measures which opened up the country’s markets to foreign interests. Corporate interests in Nigerian oil reserves, most notably Shell, ushered in wholesale theft of Nigerian resources for decades under the watch of the Nigerian bourgeoise.

This is important to note because neocolonialism has everything to do with policing in Nigeria. After the colonial police force was taken over by the Nigerian state, corporate interest in protecting oil operations in Nigeria saw investments in the expansion of the Nigerian police and military. As the Nigerian bourgeoise utilized the neocolonial relationship to increase their wealth, they increasingly resorted to the use of police violence to secure and perpetuate corruption. Today their overseas masters pull the levers while Black Nigerians control the government in name only. They control the police but have no power to shape the function or mandates of policing as a whole, which are already predetermined by the white power structure to serve the interests of the white power structure. That "independent" Black nations are still unable to eliminate the social ills associated with policing presents a problem for Rameau, who wants to believe that self-determination can provide a corrective to these ills that are inherent to policing as a whole.

Let’s circle back to his proposal for new police departments. It is curious that his position paper spends zero time delineating the practical questions surrounding what the creation of new police departments actually entails. It seems he would rather skip to describing the civilian police control board. His silence in this area should not be lost on us, for the practical application of creating new police departments is among the most precarious aspects of his argument. At the forefront of these questions is the matter of funding, specifically who is funding the creation of new police departments. This becomes important for us because as we might recall, neocolonialism establishes indirect rule primarily through economic domination:

“Economic domination usually is the most important factor, and from it flow in a logical sequence other forms of control” (Allen, 14)

Rameau goes through great pains to omit this in his position paper, but the money being used to fund his CCOP plan is coming from city and state budgets. This is the same city and state which belong to those facets of colonial governance which he identifies as occupying the Black community. Rameau seems to know how to use all the anti-colonial language to color his arguments for CCOP, but still needs the blessing of the colonizer to initiate, fund, and support his project. He manages to disguise this fact until the very end of his paper when his idealism gets the best of him and causes a slip of the tongue:

“Imagine, a low-income Black community with 100 full time, paid community workers with sophisticated communications equipment, access to government information and even vehicles.”

Very clearly, access to government information and vehicles implies access to government monies and resources. It also implies that CCOP initiatives are financially dependent on such government resources. This is a problem because it means that the real power and control is still held by the colonial state that finances CCOP, not the Black community. The financier is always the one with real power, as can be seen by the various examples of neocolonialism in which the colonial masters maintained the economic subjugation of former colonies through IMF loans and structural adjustment programs. Police departments financed by the colonial state mean that financial power can be leveraged to undermine the community control board and whatever other means Rameau thinks Black people will be able to control the police. It gives the colonial state the power to withhold funding or attach conditions and fine print to funding for its own ends.

Still, there are more practical concerns. If new police departments will be created, what of the police units who will occupy these departments? How will they be trained? Will they receive their training from the police academy? Will they be militarized? What would be their relationship with other police departments? Would they collaborate? Does access to government information include police records and databases? Would these new police units exchange surveillance data with other police departments? Would they cooperate with federal investigations, or interact with intelligence agencies? Rameau has no meaningful answers to these questions because he cannot admit to himself that the formation of new police departments does nothing to change the police in a significant way, especially when the colonial state is financing the creation of these departments.

This brings us to Rameau’s civilian police control board. He goes out of his way to reassure us that it is not your average community review board. He insists that the board has real power to make administrative decisions regarding the police:

“To be clear, the power of this body is to exercise control and power over the police, not review or oversight. This is not a review board and, at this stage in history, review boards represent a step backwards and one that further entrenches existing power relationships instead of upending them in favor of the oppressed. We are no longer satisfied with the ability to review abuses of our communities, we are in pursuit of the power to end those abuses.”

He goes on to say that essential powers entrusted to the control board include hiring and firing power, power to establish police priorities, set department policies, and enforce those policies. He envisions the board as bicameral, with these powers divided into a policy and enforcement wing. The members of these boards are either elected or, as Rameau proposes, chosen at random from residents of the police district. This random sortition is supposed to ensure that women, queer, trans, and disable people all receive an equal chance to sit on the board (even though the random nature of sortition does not guarantee board outcomes in favor of these groups). There are plenty other practical issues with random sortition, including the problem of gentrifiers being chosen to sit on the board, but I feel no need to detail them here.

The fact of the matter is, regardless of what name Rameau wants to call this board, it has no real power and might as well be just another run-of-the-mill community review board. This is because the colonial state has de-facto financial power over the newly created police departments, and one could only assume it has financial power over the control board. Insofar as membership on the board is paid rather than volunteer, the operational costs of running the board are likely funded by city and state budgets. The administrative powers that the board is supposed to have over the police department have to be underwritten by the state, since the board alone cannot force the police department to follow its mandates. In other words, it is the state who grounds the community control board’s authority over the police, not the Black community.

Because it is already subservient to the state, the board easily serves as a proxy vessel for neocolonial interests. Under the guise of anti-colonial politics the state arranges for continual policing and occupation of Black communities, this time with the illusion that those communities have control over the police. In reality, the control is purely ceremonial and at the behest of state financial power and administrative influence. It is poised to produce a community of headmen and overseers who are in the business of policing themselves and their communities on behalf of the white supremacist power structure.

We are in a moment similar to the end of the 1960’s where the state is searching for a new answer to policing its Black population after the racial uprisings of the past 6 years. It is a moment similar to the period of decolonization, where the old colonial masters were searching for a new way to maintain power over their former colonies. If we are not vigilant, community control of the police could be the state’s next solution. Black community members taking the lead to police themselves and their own communities can only do the bidding of colonialism, it cannot not in any way disrupt it or end it. Such a project can only result in continuing forms of neocolonialism. Control does not equate to power and it is not possible to vote out colonial occupation. If we are serious about anti-colonial politics we should heed the advice of its theorists and invest in armed struggle.

If Max Rameau and company truly believe that Black America is an internal colony, I leave them with this question posed by Robert Allen:

“Are black militant leaders simply opposed to the present colonial administration of the ghetto, or do they seek the destruction of the entire edifice of colonialism, including that subtle variant known as neocolonialism?”

References

Allen, Robert L. Black Awakening in Capitalist America: an Analytic History. Africa World Press, 1992.

Fanon, Frantz. The Wretched of the Earth. Pref. by Jean-Paul Sartre. Grove Press, 1968.

Nkrumah, Kwame. Neocolonialism: the Last Stage of Imperialism. Panaf, 1971.

Feldner, Maximilian. “Representing the Neocolonial Destruction of the Niger Delta: Helon Habila’SOil on Water(2011).” Journal of Postcolonial Writing, 2018, pp. 1–13., doi:10.1080/17449855.2018.1451358.

Al Jazeera. “Why Are Nigerians Protesting?” Police News | Al Jazeera, Al Jazeera, 21 Oct. 2020, www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/10/21/endsars-protests-why-are-nigerians-protesting.

City Mayors: African American Mayors, www.citymayors.com/mayors/black-american-mayors.html.

Collman, Ashley. “Sellouts to the Black Community. Traitors to Fellow Officers. Black Police Chiefs Are Caught between 2 Worlds after George Floyd's Killing.” Insider, Insider, 4 Oct. 2020, www.insider.com/black-police-chiefs-challenges-after-george-floyd-killing-2020-9.

Max Rameau, et al. “Community Control over Police: A Proposition.” TheNextSystem.org, 10 Nov. 2017, thenextsystem.org/learn/stories/community-control-over-police-proposition.