Black Against Profit (Pt. 4): From Timbuktu to Babylon

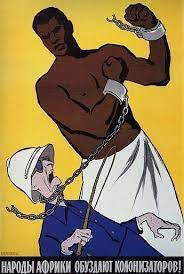

With help from Wynter, Rodney, Gomez, Achebe, and Inikori, among others, the following essay will attempt to fill in some of the missing pages of primitive accumulation, concerning all that Africa lost in the vile traffic of our people across the Atlantic.

“In 1945 Jan Smuts, Prime Minister of South Africa, who had once declared that every white man in South Africa believes in the suppression of the Negro except those who are “mad, quite mad,” stood before the assembled peoples of the world and pleaded for an article on “human rights” in the United Nations Charter. Nothing so vividly illustrates the twisted contradiction of thought in the minds of white men. What brought it about? What caused this paradox? I believe that the trade in human beings between Africa and America, which flourished between the Renaissance and the American Civil War, is the prime and effective cause of the contradictions in European civilization and the illogic in modern thought and the collapse of human culture.”

WEB Du Bois, The World and Africa, 43

In Part Two of this article series, we argued that racism predates the modern world system. Drawing from Cedric Robinson and Sylvia Wynter, our position has been that rather than being the recent by-products of modern capitalist relations, dehumanizing ideas about African people were old residue from the feudal era, that was shrewdly absorbed by Western capitalism at the dawn of euromodernity, to support the chattel slavery and colonialism of the rising white nations.

White supremacy is a material reality and never merely a question of attitudes, even when those attitudes have material effects. The historical projects of wealth transfer and political subjection of Black and Indigenous peoples from the late 15th century on, that are behind Europe's accelerated industrialization from the 17th century, also explain global white hegemony in the late 19th century – far better than any purely culturalist explanation, like the Weberian approaches that explain the story of Europe's rise by an accidental alignment of successful values, that gave universal validity to its achievements (Amin, Eurocentrism, 26-27).

Historical materialism is therefore quite helpful for explaining much about the antagonistic relationship of Black labor and white capital. Yet as we have seen (in Part Three), it does not account for why its discoverer, Karl Marx, was equally as susceptible as his bourgeois targets to racist, even pro-imperialist arguments about the colonized world's economic, cultural, and political relationship to Europe; why he abandoned empirical methodology at the crucial moment, choosing not to contest Hegel's infamous claim about the African subject's exclusion from History.

With help from Wynter, Gomez, Rodney, Achebe, and Inikori, among others, the following essay will attempt to fill in some of these missing pages of primitive accumulation, concerning all that Africa lost in the vile traffic of our people across the Atlantic. In Part Five, we will conclude by describing the dialectic of Black labor in the capitalist West, before summarizing our project's implications for the general study of capitalism and racism.

Due to the unusual length of this entry, I am providing an outline for each section in advance, as a kind of table of contents for the reader's convenience.

I. Precolonial Society and Culture in West and Central Africa

- Precolonial African Philosophy: Supreme Being and Vital Force

- Gender and Sexuality as "Transgressive Chaos"

- (Parenthesis: A Mind of Our Own)

- Communalism and Class Antagonisms in Africa

II. Contradictions of Statecraft in Medieval and Early Modern Africa

- "The Lion Has Walked": Recreations of History in Imperial Mali

- Kilombo and Cross: Political Transformations of King Njinga

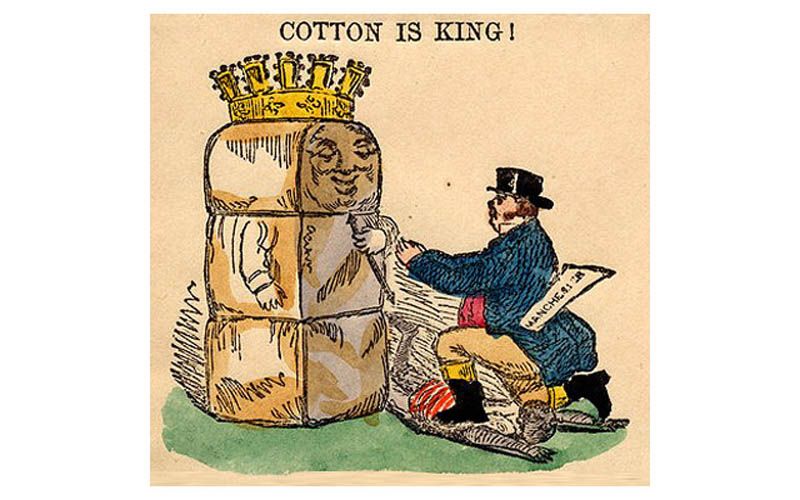

III. Rejected Stone/Cornerstone: African Labor in the Making of Capitalism

- The Slave "Trade" and African Underdevelopment

- Capitalism, Slavery, and the Rising White Nations

I. Precolonial Society and Culture in West and Central Africa

What kinds of peoples did the Portuguese encounter when they landed on the Guinea Coast in 1471 CE? What were some of the general social and cultural characteristics of the Black nations supported by what Diop and other historians have controversially described as the “African mode of production”?

To start with a common observation, it's clear that Africans in the mid-fifteenth century did not yet see themselves as Africans: as a totality of related cultures, united by the geographic boundaries of their mother continent, who have a corresponding set of shared interests wherever they live. Instead they usually saw themselves as the members of distinct nations, held together by relations of commerce or conquest, and sometimes by religious faith.

It is true that ancient regional histories tie together distinct ethnic groups across Africa, who may speak related languages; have similar customs and forms of social organization; or uphold centuries-old patterns of cooperation or competition, in one country or many, that help define the identity of each group. As we will see in the next section, that is true for the Mande peoples of West Africa, like the Soninke and the Bambara; and also for the Bantu peoples of Central Africa, such as the Bakongo and the Mbundu. Furthermore, the need to protect regional economies from foreign conquest, and from the social dislocation caused by slave raiding, was an urgent stimulus to political unity across ethnic lines; and this was normally attempted by ethnic groups whose military and economic power made them hegemonic over others. So African empires would sometimes impose aspects of the ruling group's national identity on their provinces, exchanging protection for acculturation; as when Mali imposed Malinke laws and social conventions on the Songhai – more on that in the next section, too. But these cultural, economic, and political-military grounds for regional integration in the pre-colonial period did not yet yield a Pan-African consciousness of the kind that is described above.

In truth it was the slave-trading European –and also the Arab and (nonblack) Amazigh of the Trans-Saharan Trade – who first melted our distinctions down into the pool of heathen, homogenous otherness, called the "Negro," the "Moor," the "Ethiopian," or the "Zanj," depending on the oppressor's tongue. This was done not only to legitimize the slave trade post facto; though it did have that convenient use for inchoate capitalism, which could not have conquered the world without chattel slavery. More than an ideology used to justify profits, antiblackness has historically been fundamental for the subjective understanding of those non-black peoples who have oppressed us: in elaborating a system of symbolic representation that develops exclusive claims of humanity, for the group to whom a particular individual feels responsible, given the limited resources and competing claims of all human groups under pre-cosmopolitan visions of the world.

As Sylvia Wynter explains in "1492: A New World View" – an indispensable text, to whose arguments this essay repeatedly turns – the "stereotyped image" of the dehumanized Black has played a similar role for the cultural imaginary of slave traders in North Africa, as it did for that of the fledgling capitalist class in Southern Europe, despite the very different political-economic contexts of their respective encounters with Black people (20-21). Whether in Arab-Islamic or Euro-Christian cartography, the boundary with Black Africa has marked the limit of the rational, the providential, and the acceptably human. Below the Sahara, unaccountable horrors awaited the monotheist of white skin; who had never tasted human flesh, and therefore had to fear for his own, in the land of infidels. Just as the entirety of Africa formed a "Dark Continent" for the European traveler, whose own humanity was coded in contrast with the Moors in Southern Europe.

However, there must be more than this negative basis for African unity. Some positive basis must surely exist, that allowed for the amalgamation of "universal elements of West African culture" (Blassingame, The Slave Community, 2-5), witnessed in the birth of New Afrikan communities of North America. That unity does not have to resort to biological essentialism – the belief that all Black Africans have a shared genetic makeup – nor to vague metaphysical constructs, like the unhistorical "African Personality," to explain what real grounds we have for unity in the face of Africa's enemies.

In The Cultural Unity of Black Africa, CA Diop very ambitiously argued that continental unity was possible owing to the shared cultural practices of all Black Africans, which he believed points to their common origin in an earlier cultural complex in Egypt. With painstakingly gathered, if sometimes unconvincing evidence from anthropology, philology, and written and oral records, Diop made the case that our social, political, and cultural affinities result from the ancient dispersion of Nilotic peoples throughout the Continent, following the decline of pharaonic Egypt and of Nubia, its historical source and successor.

Our task in this first section is more modest, and unconcerned with the ultimate provenance of Sub-Saharan cultures. We will describe some of the similarities of worldview and way of life of those West and Central Africans who were stolen away by the Atlantic Trade. Whose descendants forged a Pan-African culture right here, in the imperial West; like ironworkers from Nok, thrown to the furnace of Babylon.

Since a systematic treatment of these primary elements is a specialist's task, we have to limit ourselves to the following topics: the character of African philosophy, in particular its metaphysics and the ethical-existential implications that follow from it; gender and sexual categories in pre-colonial Africa, and their great danger for our oppressor's categories; and class stratification and wealth accumulation in the Black societies that Walter Rodney describes as "transitional" forms between communalism and early feudalism (How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, 68-69).

Precolonial African Philosophy: Supreme Being and Vital Force

African traditional religions (ATRs) are systematic responses to perennial questions that have exercised philosophers from Europe, Asia, North America, and everywhere else that human beings are found. For human beings everywhere have posed fundamental questions about life's meaning, and tried to answer them with some degree of logical consistency. In discussing their content below, I am not advocating for any particular African religion, or for religion in general. I am only summarizing some of the advances in speculative thought made by precolonial Black Africans, which have a religious rather than a secular character in traditional (non-Westernized) societies.

Despite many differences in content, ATRs tend to agree in broad outline on the origin and nature of the universe, and our place within it. Unlike the stark anthropocentrism of the Christian West, where Man is sovereign of the world by his Father's appointment, and answers to Him alone, African cosmologies insist that human beings are invisibly tethered to all other beings – living or nonliving –that inhabit or interact with our world. Permanent links of causation zig-zag the divine and ancestral, the human and natural realms; and beings in each of these realms – better understood as distinct existential registers of a single shared reality – are capable of influencing inhabitants in the others, sometimes in very surprising ways. That influence is achieved through the continuous interchange of a primary creative or vital force that dwells with-/in all beings, and that radiates with differing degrees of power, depending on the being's place in the cosmic order.

An exemplary cosmology of this type is found among the Baluba, a Bantu-speaking people of Central Africa, and one of those more heavily impacted by the Atlantic Slave Trade.

In the classic (and contentious) study Muntu: African Culture and the Western World, Janheinz Jahn outlines the general scheme of classification for Bantu ontology ("logic of being", or study of the meaning of being itself). It is important to note in advance that some of Jahn's sources, especially the Belgian missionary Placide Tempels, and the Rwandan Catholic philosopher Alexis Kagame, have come under fire by more recent African philosophers, who accuse them of wrongly interpolating Western ideas into Bantu thought by way of spurious analogy. (For critical discussions of Tempels and Kagame, see Serequeberhan's African Philosophy: The Essential Readings.) Jahn himself could also be accused of making broad interpretive leaps across the cultures of quite diverse historical groups, so as to reductively describe the African outlook as a whole. Nonetheless, Muntu does at least provide us with the basic categorial concepts of the Baluba system, helpful for characterizing Bantu metaphysics as a whole.

For the Bantu, there are four cardinal categories of existence: Muntu/Bantu (human beings, who share this classification with ancestors and with God, as beings having intelligence), Kintu/Bintu ("unintelligent things", living or inanimate, including all animals), Hantu (space and time), Kuntu (modality). Each category refers not to an underlying material substance, but to a still more primary creative force (known as NTU), which is everywhere and comprises all things. The qualities of every existing being – what makes them "be" in a particular form –result from infinitely diverse arrangements of NTU, according to these four basic ontological categories, which is why they each have that term at their root (Muntu, 100-101).

The idea of causation in Bantu cosmology is especially profound, since it accords a distinctive place for human rationality without rendering us all-powerful, in the manner of Western-technocratic reason. Nommo, translated as "the word," is the great power held by all Bantu (whether human, ancestor, or god) to summon living things into being (102). The nearest cognate in Western thought is probably the logos of the Greeks, by which means God engenders the world in the biblical Book of John. Yet that translation would still be inadequate, since nommo is a power of creation shared by all intelligent beings, one that allows humans to transform reality according to their own unique plan, with the power of the spoken word. And as we mentioned earlier, entities at any level of being in Bantu cosmology can influence those in others, either by enhancing or draining the patient's share of creative force (115-116). That is not only true of interactions between intelligent beings, where their influence is exerted through deliberate speech, or in those instances where intelligent beings act upon the Bintu. It is also true for the effects that inanimate things can have on a Muntu: as when, in traditional medicine, salt is administered to a victim of zombification, replenishing their supply of vital force in order to restore them to life (130).

In this boundless play of dynamic forces, there is no room for anything like an atomic, self-sufficient idea of Man – the chimera that has plagued bourgeois thinkers since Descartes; whose lack of attachments beyond his own self-interest poses many unsolved problems for ethics and politics in the West today.

Philosopher Kimbwadende Fu-Kiau provides further details of the Bantu conception of life, that indicate how closely the Bantu genius has reached similar conclusions about the natural world as contemporary Western science, albeit in a highly poetic idiom. In his African Cosmology of the Bantu-Kongo, Fu-Kiau interprets esoteric meanings of the pictographic language by which his people disclose their ideas on the nature of the world.

According to the Bantu ideograms, our universe begins in paradox. A straight line represents mbungi, the emptiness or nothingness of the world prior to its beginning, that is also said not to be nothing, as in creation ex nihilo; but instead is believed to harbor many inert "active forces", that lack dynamism and form; they are only potential being (17-18). The world is finally created when a so-called fire-force, "complete by itself", emerges from this pregnant nothingness, throwing the inert powers of mbungi into motion. The undying principle of change or becoming (kalunga) that is sustained by the movement of this force, eventually engenders the Earth (20) as well as an "immensity...that one cannot measure" beyond it (21): presumably the expanse of the entire universe.

In addition to suggesting that the Bantu have an indigenous concept of infinity, represented by the immeasurable extent of the cosmos, their cosmogony also suggests that they believe in something like the Big Bang – a connection that Fu-Kiau makes explicit in his work. Interestingly, though the Bantu do have a geocentric conception of the universe (which would seem to suggest an anthropocentric world-sense), they also believe that there are other inhabited planets in that universe – a possibility never entertained by the Scholastics of medieval Europe. The Bantu cosmogony explains that the gradual cooling down of the fire-force in the other planets, until they are finally able to sustain life, is the climatic condition for that possibility: which is not far from the contemporary scientific explanation for why Earth is uniquely suited in our solar system to support life (22-23).

Much of the modern prejudice against exploring the merits of traditional African thought stems from the Abrahamic contempt for polytheism, which is often regarded as a lower stage in the mental and moral development of Western Man. African polytheism has been disparaged as mere "animism" or "fetishism" by that discourse, which prides itself on the comparative sophistication of its concept of God. It is assumed that African polytheism, conceived as a kind of nature worship, evinces less capacity than monotheism for abstract theological ideas like the unity, omnipotence, and omnibenevolence of a God who stands above His creation. This "fact" is then held to confirm the African predisposition toward mimetic (imitative) and crudely empirical modes of thought, and our related inability to think universally and abstractly. But the truth is that traditional African religions conceive of the Supreme Being in ways that are no less sophisticated than the philosopher's God of Islamic Spain, and that are surely more advanced than the personified God of popular Christianity.

The highest ontological principle in African reason – that which sustains the world as the wellspring of all creative force, as author of the laws that govern its orderly transit through the cosmos – is casually translated as "God" in the English-speaking world. But the African concept of the Supreme Being should not be confused with the personal God of Western monotheism, who is widely portrayed with human feelings and motivations, and always assigned with a male gender; who can be swayed through prayer and supplication to show mercy – like a father who feels that his child has learned her lesson, and has decided to retract his punishment.

Historian Nwando Achebe explains that the Supreme Being is known by many names across African cultures. They are called Chukwu by the Igbo of eastern Nigeria, Ngai by the Kikuyu and Masai of Kenya, uNkulunkulu by the Zulu of Azania (southern Africa), Imana by the Ruanda of Tanzania, Meketa by the Kono of Sierra Leone. Across these diverse systems, the same paradoxy reigns in opinions on the nature of the Supreme Being. They are said to be totally transcendent of matter and space and time, and yet somehow always present with Their creations. They are an entity that is impossibly remote from the concerns of human beings; but They are also present in the smallest movement of dust, and equally in the big affairs of kingdoms, as the prime force that underlies all phenomenal change (Female Monarchs and Merchant Queens in Africa, 37-40).

Dismissing outright the colonial lie that the African mentality is irrationalist, we can see that the paradox of the Supreme Being invites interpretive comparisons from the critical theology of the West; where early modernist thinkers tried to reconcile belief in an all-powerful God, with the apparent determination of nature, according to scientific laws. From this changed perspective, it is arguably the case that the nearest cognate of the African God in Western thought is not the crude, anthropomorphic God of popular Christianity, but rather the God of pantheism: "Spinoza's God," as Einstein famously described Them.

The Supreme Being of the African is everywhere, and because of that They are nowhere (in particular). They are the source of all potency; and Their "remoteness" from the believer refers to Their incomprehensibility and terrifying power, rather than their "physical location", which is as expansive as the universe. This is all fairly consistent with the pantheism of Western philosophers like Giordano Bruno and Baruch Spinoza, who were persecuted for rejecting the anthropomorphic God of the Bible. Again, the Supreme Being effects changes in nature strictly according to the laws that govern creative force, and never from any personal desire to intervene in an established course of events. This point especially is redolent of Spinoza's pantheism. In the Theological-Political Treatise (1670), Spinoza controversially rejected the possibility of God's miraculous intervention in nature, claiming it would be an affront to the scientific laws by which He Himself had ordered nature, according to His own perfect wisdom.

Sylvia Wynter has noted that the belief in incontrovertible natural laws, and the corresponding rejection of miracles, on the grounds that a perfectly wise God would not establish such laws only to later subvert them in violation of (God-given) reason, was key for the development of Western science away from the theocentric idea of the cosmos and toward a humanistic one, wherein the universe was created for us (propter nos) rather than to express God's inscrutable glory; was therefore intended to be understood by us ("1492: A New World View", 27). The belief in God's supreme aloofness is closer to the Western-modern scientific mentality, than is the anthropomorphic miracle-worker of the Old Testament.

While most ATRs do not place the same stress as the Western rationalists on the full comprehensibility of God's creation, on the whole they can be said to share the early modern belief in the Supreme Being's impersonality, and in the inviolability of Their ultimate design – a belief that quite literally announces itself as the doctrine of predestination, in representative texts of the pre-colonial Weltanschauung, like the Sundiata epic. (It is important, however, to note that a distinction has been identified between predestinarian and voluntarist schools of thought in pre-colonial African philosophy. See Henry, Caliban's Reason, 36.)

On this adjusted view, African polytheism seems less "crudely empirical" than the monotheists would like to believe. It might be said that the orisas of the Yoruba, the abosom of the Akan, and the many other pantheons of subordinate deities recognized in ATRs, serve similar roles of protection, guidance, and admonishment for human beings, as does the monotheistic God of Abraham; and unlike the monotheists, the petitioner in ATRs can meet these psychological needs without diminishing the supreme God's glory, by asking Them to change all reality on behalf of one of Their creations.

In fact the ATR practitioner, like the pantheist on the threshold of modern Biblical criticism, could even reproach the Biblical God for being crassly anthropomorphic. After all, to which prayer between two imperfect human rivals should an all-knowing, all-loving God respond in their conflict? What intervention on the behalf of one or another party would not lower the dignity of a Being That is responsible for countless planets, for many dimensions beyond our own; and how could the prayer of a finite human ego ever comprehend all the vastness that Their plan contains well enough to justify changing it?

The polytheism of pre-Christian, pre-Islamic Africa would appear to be a novel solution for reconciling the concept of God as the highest idea of Being – too abstract, too immense and powerful to be swayed by human wills – with the universal and deeply felt human need for guidance by a higher power, who is still close enough to the human personality to be interested in the outcome of our affairs. If not a perfect solution for the problem of divine intervention, the case can be made that it is at least a more thoughtful one than the popular idolatry of the Catholic Church.

In light of all this, one may wonder why the ATR practitioner even bothers to show religious veneration for the Supreme Being at all? Why pray, sacrifice, and worship to a Being that is indifferent to your devotion?

Perhaps this very loftiness of the Supreme Being of Africa, considered together with the holistic character of African metaphysics and ethics, may help explain the reverence and fear that believers must have for a God who cannot directly help or harm them. Humanity must give the highest praise and consideration to this Being, though They cannot be affected by insult or influenced by prayer, because forgetfulness of this Source of all power tends to damage the individual ego's holistic sense for how any other invisible, or apparently insignificant powers in our deeply interconnected world, can assist or undermine our (limited) designs.

According to Paget Henry, the negation of the ego by events beyond its power to control, is a cornerstone of the ethics of African existentialism. Its ideal result is to limit the claims made by the individual personality on the social collective, and to readjust the rebellious ego to the order of super/natural forces, sustained by the Supreme Being, that leap forth suddenly to destroy her carefully laid plans (Caliban's Reason, 32-33). On this view, it is to the advantage of the believer, whether plotting for good or evil, to remember that her cleverness and strength are limited, while the wisdom and power of the Being that sustains all things is not. And They are with us always, ready to defend Their design from petty conspiracies of the ego, through the generation of forces that are hidden and unpredictable, waiting like landmines for the wicked and unwise.

Whether one chooses to believe in One God, many gods, or no god at all, it is evident that African traditional religion encompasses a wide range of carefully considered opinions on ontology, cosmology, ethics, and philosophy of existence, that are elaborated at the highest levels of theological abstraction. It is simply not true that any non-African system of religious thought had to shed light on the so-called Dark Continent. The best any of them could do is illuminate our independently arrived truths about existence from interesting new angles.

Gender and Sexuality as "Transgressive Chaos"

Because the Supreme Being is not really a person, but rather the highest ontological principle of reality, it is unsurprising that when They are ritually personified, They are not assigned with a consistent gender across cultures. The very nature of African languages makes the task much harder, as African languages lack gender-specific pronouns (Female Monarchs, 40). But the more basic challenge for each African people is determining which gendered traits are primary for their given conception of Being as a whole.

For instance, Mwari of the Shona people has some attributes that are traditionally associated with men as well as women in that southern African culture; but the majority of Their characteristics are connected with motherhood. This is also true of the matrilineal Nuba people of the Sudan, whose Creator is depicted as a woman. In several African cultures the Supreme Being is even explicitly described as genderless, as with Emitai of the Diola in Senegal, or Chukwu of the Igbo in Nigeria. And in Kenya, Ngai is held to be without gender, yet is sometimes referred to as "She" in prayers (Female Monarchs, 43-44).

What all this apparent "gender trouble" really indicates is that there was less trouble about gender categories in traditional African societies than in the Christian West. The reason that the Shona traditionalist can countenance a Supreme Being that is motherly or feminine, is that the stigmas about weakness or inferiority of the labor associated with women in the West, are altogether foreign to Shona values.

To be clear, this does not mean that gender oppression doesn't exist in African societies, traditional or otherwise. It is also not a uniform statement about the nature of gender relations across African cultures. What it does mean is that the peoples who were stolen from "heathen" countries typically had less intolerant and rigidly binary ideas about gender (and, as we will see, sexuality) than did their Christian captors.

In practical terms, it meant that unlike their coevals in Europe, African women, and other categories now marginalized in the "colonial-modern gender system" (Maria Lugones), were not automatically excluded from leading roles in government, commerce, and culture in the precolonial years of European contact (15th through 19th centuries). This is plainly the case for the Igbo, an acephalous (stateless) people of eastern Nigeria, that were one of the largest ethnic groups impacted by the Trans-Atlantic Trade. As Achebe explains:

"In the small-scale societies of precolonial Igboland, eastern Nigeria, leadership and power were not alien to women. Their position was complementary rather than subordinate to that of men...The Igbo had two arms of government, male and female. Female government was further divided into two arms, the otu umuada and otu ndiomu-ala...

The otu umuada act as political pressure groups in their natal villages. They create unifying influences between their natal and marital lineages. They settle disputes between women. They also settle intralineage disputes and disputes between their natal villages and the villages in which they are married. In fact, the otu umuada were the supreme court of society" (Female Monarchs, 96, emphasis added).

The Igbo political system relies on a dual-sex, complementary idea of democratic rule: where power is accorded to age-sets within lineal groups, rather than to royal families, priests, or some other distinct stratum of political authorities that can rightfully be called the state.

But even this structure should not be taken to mean that throughout precolonial Africa, binary gender identities and corresponding social roles neatly aligned with what Western discourse calls "biological sex." Achebe further explains that

"In Africa, sex and gender do not coincide; instead, gender is flexible and fluid, allowing women to become men, and men, women, thus creating unique African categories such as female husband, female son, and male priestess. The flexibility and fluidity of gender roles translate into leadership. Some exceptional African women have been able to transform themselves into gendered men in order to rule their societies, not as princesses or queens, but as headmen, paramount chiefs, and kings" (131).

Indeed, the gender fluidity of precolonial Africa, and its social and political implications for naturalized gender notions, have always drawn revulsion as well as fascination from Western Man. Wynter argues that, within the system of symbolic representation of the secular West, the African stands for the "transgressive chaos" just beyond the horizon of rationality, inhabiting a region that secular-statist Providence has abandoned; a region of licentious and bloody scenes of the purely instinctive life ("1492", 21).

And in the encounter with Africans, nothing is more unaccountable, nothing pulls Man away in the current of unreason quite so powerfully as our violations of naturalized gender. After all, Western Man has always supported the belief in his own rationality, and his resulting right to dominate, by enforcing the idea of its inadequate development in the "opposite" gender. The variable gender norms of African people, who are already the negation of rationality in our very bodies, can only appear that much more to violate every canon of political Reason: from the biological foundations of gendered behaviors and outward presentation, and corresponding ethics; to the validly gendered labor division, that confines non-Man to devalued, reproductive work in the household; to the necessarily patriarchal character of the State, founded on (superior) male violence and kept running by (superior) male powers of abstraction.

So for Hegel, who was arguably the greatest Western philosopher, the reports from Angola of an "inverted world," wherein a woman (Njinga) ruled a powerful state as a king; employed women in military service; and reduced her male lovers to the social status of women concubines, all confirmed his long-held view that Africans are a people outside History, untouched by the logic of freedom that has progressively unfolded through the centuries (Linda Heywood, Njinga of Angola: Africa's Warrior Queen, 250).

Closely related to Man's anxiety around gender is his contempt for African sexuality. Precolonial African societies recognized a plethora of sexual behaviors and identities that, under current regimes of colonial-sexual oppression, would be called queer. Hundreds of examples can be referenced from across the continent.

In Northeast Africa, there are reports of regular same-sex practices in Eritrea, and among the Harari, Galla, and Somali (Murray and Roscoe, Boy-Wives and Female Husbands, 19-20). “Males” with alternative gender identities are acknowledged among the Amhara of Ethiopia, and gay marriage is practiced among the Krongo and Mesakin peoples of the Sudan (22). In Central Africa, Evans-Pritchard reports that there was no stigma against same-sex relationships among the Zande royalty, where such relationships were institutionalized among the princes, and were usually formalized through gift-giving acts to the receptive male partner (24). Lesbianism was also regularly practiced in Zande society (26). In Angola, Kurt Falk reports first-hand testimony of regular same-sex activity, that has formal local designations, among the Wawihe, the Ovingangellas, and possibly also the Nguni peoples (163-165).

Among the Imbangala of Kongo-Angola, whom we shall describe later in more detail, there was a special category of the priesthood, known as the Ganga-Ya-Chibana, whose occupants today would probably be considered transfemmes. There are problems with the main description we have of the Ganga’s sexual practices, which is provided by an outraged colonial reporter. Among other issues with this testimony, it is unclear if these practices should be described as homosexual, considering the ambiguous gender identification of the priesthood. But this much is clear: that the Ganga dressed and performed gender in ways that are usually associated with the women of Imbangala, and moved freely in the quarters of women, unlike their male counterparts; that there was a direct association of their sexual predilections with their spiritual potency and function in the society; and that certain privileges and exemptions from relationship taboos attached to their position, which was a government advisory and ritual officiant role of premium importance for Imbangala camps (161-163).

The accounts of early European explorers who encountered African homosexualities were routinely disparaging, drawing on the repressive Christian values of a “rhetoric of abomination,” for which all non-marital, non-heterosexual eroticism was held to be equally perverse:

“Before the 18th century, European writings on sexuality were nearly always part of a moral discourse in which sexual identities, roles, and acts were represented in the terms of a Judeo-Christian code. In this code, all forms of extramarital sexuality and certain forms of marital sexuality were to one degree or another sinful and defiling, and everyone was believed to be at risk for the temptation and lust that led to such acts. The code was uninterested in why some sinners lusted for the same sex and others for the opposite—both were “foulest crimes.” Indeed, the very nature of lust was believed to cause a breakdown of moral consciousness and the ability to discriminate between proper and improper sexual objects. Hence, homosexuality, incest, bestiality, and other sexual acts were all viewed as transgressions that occurred when individuals no longer recognized distinctions of gender, kinship, age, race, and species—an “undifferentiated” state of consciousness that Europeans also attributed to people they considered “primitive” (9).

With the shift of Western consciousness away from Christian-moralist towards secularized, scientistic views on sexuality – never divorced from essentialist views about race and gender in the anthropology of the 19th century – the European discourse on African homosexualities ramifies in two distinct directions. The first was “humanistic” homophobia, which constructed African homosexuality as a by-product of inadequate sexual restraint, of the necessary type for maturation toward adult gender roles and civilized conduct in general (10-12). The second direction was taken by advocates for the normalization of homosexual practices in Western societies. On a variation of the “noble savage” theme, writers like Kurt Falk and Gunther Tessman would argue that homosexual desire, rather than being abnormal, was perfectly natural, based on the widespread evidence of its acceptance in African societies, which were held to be closer to uncorrupted human nature than the supposedly civilized West (13-14).

This primitivist fallacy is, of course, simply the reverse side of the quasi-Freudian, repressive hypothesis of the academic homophobe. Both positions assume that African cultures represent a less advanced stage of human development than what obtains in the “civilized” West. Both attempt to construct Western identity by reference to a primitive “other,” assumed to be closer to nature, either in rejection or romantic embrace. Again, in the Western attitude to precolonial sexualities, we can see that African otherness is a stabilizing point of reference for the subjective understanding of the white Man.

As we have seen in our prior discussion of "God," a pressing problem with the translation of African categories into the language of the oppressor is that their English, French, Portuguese cognates are often laden with colonial assumptions absent from the original idea. The result is a distortion of African thought by Western Man; who, like Nietzsche's ascetic priest in The Genealogy of Morals, starts by pathologizing our cultures, in order later to administer his own (colonial-)Christian cure, which is no less sickening to the patient.

This appears to be the case even with the translation of traditional gender terms as "man" and "woman," as the Nigerian sociologist, Oyeronke Oyewumi, makes clear in The Invention of Women, her radical study of precolonial gender relations in the Oyo kingdom:

"In the Yoruba world, particularly in pre-nineteenth-century Oyo culture, society was conceived to be inhabited by people in relation to one another. That is, the "physicality" of maleness or femaleness did not have social antecedents and therefore did not constitute social categories. Social hierarchy was determined by social relations...[H]ow persons were situated in relationships shifted depending on those involved and the particular situation. The principle that determined social organization was seniority, which was based on chronological age" (The Invention of Women, 13).

The Yoruba terms that are redefined as "male" and "female" by Western anthropology do not in fact indicate a gender binary that places men at the center, as does the category "man" that lies at the root of "woman" in Western cosmo/logics:

"I should immediately point out that the usual gloss of the Yoruba categories obinrin and okunrin as "female/woman" and "male/man," respectively, is a mistranslation. This error occurs because many Western and Western-influenced Yoruba thinkers fail to recognize that in Yoruba practice and thought, these categories are neither binarily opposed nor hierarchical. The word obinrin does not derive etymologically from okunrin, as "wo-man" does from "man." Rin, the common [non-gendered] suffix...suggests a common humanity; the prefixes obin and okun specify which variety of anatomy (Invention, 32-33).

Oyewumi further explains that because these terms are not generic bodily descriptors of a gender dualism that runs throughout Yoruba cosmology, they do not apply to "male" and "female" animals, which are called "ako" and "abo," respectively (33). For the convenience of English readers, and to correct hierarchical associations of "biological sex" and gender that are Western importations, Oyewumi coins the terms "anamales" and "anafemales." These neologisms mark the two types of anatomy that are traditionally required for reproduction, but that are not indicative of either hierarchical difference or of sexual dimorphism in traditional Oyo (35).

Oyewumi's argument, contra feminisms that naturalize the conflict of genders at the center of Western life, is that the forms of gender oppression that are visible in non-Western societies today do not necessarily indicate an original, hierarchical division of genders in pre-colonial periods. Again, she is not saying that African gender relations throughout Africa were uniformly egalitarian before the white Man came. Her point is only that where binary gender oppressions do exist in colonized nations like today's Nigeria, they should be carefully studied from an African standpoint, to determine whether they don't in fact belong to the colonial reordering of reality, rather than to the autochthonous world-sense of colonized people:

"The challenge that the Yoruba conception presents is a social world based on social relations, not the body. It shows that it is possible to acknowledge the distinct reproductive roles for obinrin and okunrin without using them to create social ranking" (36).

Oyewumi's criticism extends over the whole of Nigerian historiography, as it was pioneered by Rev. Samuel Johnson in his The History of the Yorubas (1921): a work infected by the "male-biased gender ideology" of Johnson's colonial training. She notes that even though Johnson's own account indicates that some of the alaafin (traditional rulers) of Oyo were actually obinrin, he keeps to his theological-colonial training by falsely rendering the king's list as all men, in the Western-binary sense (86-91).

(Parenthesis: On Having Our Own Mind)

Our earlier note of caution about translating African names for the Supreme Being as "God," or its equivalents in other colonial tongues, forms a logical duo with Oyewumi's denaturalizing critique of Western feminism. Oyewumi's position is that Western feminism wrongly extrapolates from Western gender ontology, to naturalize a conflictual model of two socially unequal genders that applies trans-historically to all humanity. She believes that African feminist scholarship is hobbled in its efforts to theorize gender from an African standpoint to the extent that it carries this presupposition into the study of our indigenous cultures.

Her point can be extended to any critical-theoretical tradition of the West that has been repurposed in the interests of African people. African Marxisms, anarchisms, and feminisms can't truly be called critical when they blithely adopt research programs designed for patterns of social conflict in the Global North. When we first accept that social categories and trends of development that are particular to Europe must be discoverable everywhere else, we thereby resign ourselves to an imitative relationship with the metropole, to a lifetime of squeezing social and cultural realities in Master narratives that don't fit.

Anyway, for such a mimetic approach to even be consistent, it would have to follow the Master narrative all the way up to the present. And since the Second World War, modernist and post-modernist thought in the West have either struggled against or embraced the insight captured in Heidegger's aphorism, that "language is the house of Being." Every human discourse moves in an element of tacit cultural assumptions ("fore-understandings") that are specific to its geographic and temporal origin, and without which its objects cannot fully "be" in the sense they are intended by the speaker. Even to stay current with the trends in Western thought they would like to imitate, then, critical theories of African liberation, and the practices they inform, first have to drop the naive view that categories from one cultural complex can be aprioristically applied to our own, without effacing the phenomenon they hope to describe.

This does not mean that liberation theory should discard any notion of universality or objectivity. To the contrary; the destinies of African and all colonized people are irreversibly shaped by the same rapacious global capitalism, which is primarily but not exclusively Western-humanist in cultural origin and outlook. And that is an objective truth, that poses universal problems for the world's dark majority.

But what it does mean is that the Master's tools – Western theory and practice –should be used, when they are useful at all, to dismantle the structures that Man has planted on top of us, in preparation for setting afoot a new Humanity. We should not be retrofitting realities where they never existed for precolonial societies, simply because a "modernizing" discourse insists – on the authority of Marx, Weber or Foucault, of De Beauvoir or Butler – that those realities ought to be present anywhere that is acceptably human.

As Oyewumi wonderfully summarizes this point:

"Self-reflection is integral to the human condition, but it is wrong to assume that its Western manifestation...is the universal. In the era of global capitalism, Coca-Cola is universal, but it is hardly inherent in the human condition" (Invention, 22).

Lastly, this parenthesis does not suggest that we should be romantic or uncritical in the study of African life. In an earlier criticism of Marx's "Asiatic mode of production" (Part Three), for instance, we argued by way of Diop that complex mediations of caste in Africa likely had an arresting effect on those tendencies that led to social revolution in other parts of the world. In what follows, we will draw attention to further contradictions of traditional African life, that in this case lent themselves--however unconsciously--to the enormities of the Atlantic Slave Trade, and the long-term weakening of Africa's defenses against Western imperialism.

Communalism and Class Antagonism in Africa

A commonplace in anti-colonial discourse, found for instance in the writings of Ahmed Sekou Toure, is that capitalism is foreign to the African mentality, since class stratification had never really taken hold in our homelands. Our societies were inherently communalistic, if not fully egalitarian, before the advent of colonialism, and therefore socialism rather than capitalism is the system of productive relations that best expresses African values in the modern world.

Historical ideas developed in political struggle are never politically innocent. And in the fight against classical colonialism, the negation of class struggle was often the sleight of hand by which particular class and bureaucratic interests were passed off as the interests of entire nations. Conveniently for Sekou Toure's Democratic Party of Guinea, for instance, Africa's supposed freedom from class antagonisms was the justification for the one-party state. For decades, opposition parties (not only petty-bourgeois, but also Communist) were outlawed in Guinea, on the specious reasoning that a plurality of parties in a given nation can only ever express multiple and countervailing class interests – a condition that was obviously not met in pre- or post-colonial Guinea, on Toure's account (Rajen Harshe, "Guinea under Sekou Toure," 624).

Bad as this reasoning was, there is still a kernel of historical truth in Toure's communalist rhetoric. To be clear, there always was and continues to be vigorous trade activity on the local and trans-regional levels throughout Africa; and this was/is often directly organized or supported by political elites, to their own considerable economic advantage. That activity alone might have been enough, given an uninterrupted process of private accumulation in West Africa, to ensure the rise of sharp class antagonisms there – for example, in pockets of the Sahel, the Maghreb, and the southern forest zone, connected through the Sahara Trade, or the busy trade routes along the Niger and Senegal Rivers. Yet compared to the mercantile West, it is true that in Africa private property relations, and the legal notions of property that would have encouraged the growth of a modern bourgeoise, were largely absent by the time Europeans made first contact. It is fair to say that with some feudal, and even some nascent capitalist economic elements in tow, the vast majority of pre-colonial African societies still remained organized largely on communalist lines.

Just what is communalism, anyway? Walter Rodney describes African communalism in the following terms:

"In Africa, before the fifteenth century, the predominant principle of social relations was that of family and kinship associated with communalism. Every member of an African society had his position defined in terms of relatives on his mother's side and on his father's side. Some societies placed greater importance on matrilineal ties and others on patrilineal ties. Those things were crucial to the daily existence of a member of an African society, because land (the major means of production) was owned by groups such as the family or clan--the head of which were parents and those yet unborn" (How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, 36).

The extended family unit, Rodney goes on to say, was also the basis for labor recruitment: for large-scale farming projects that could not be supported on small family-owned plots, and for other economic activities, such as hunting and fishing. The fruits of this collective labor would also be distributed on a kinship basis, according to the immediate need that brought family members together for those joint activities, rather than that product accruing as surplus to an individual owner (36-37).

Since the land was owned in common by extended family groups with an ancestral claim on the territory, and was parceled out according to the needs of the entire kinship group or clan, it could never become the private property of an elite, who could then compel the majority to work on their behalf – as was the case under feudalism, and other economic systems based on degrees of private ownership of the means of production.

This is more or less the basis for the claim that African communalism is best expressed in contemporary, (post-)industrial conditions of life, by socialism, the social ownership of the means of production – including land, but also water, tools, factories, and the other essential factors for the production of useful goods on a national and industrial scale.

As a Marxist, Rodney maintains that while communalism is the prevailing economic mode throughout ancient and medieval Africa, it is nonetheless a stage of development that all societies have passed through in their march toward private property and class inequality (39). It is not some charmed, permanent feature that is unique to African people, as in Toure's model. Nor is it something to be celebrated without qualification, as though the comparative absence of class exploitation under communalism is without its own problems. In fact, since Rodney considers class struggle to be the motor of historical development, he argues that communalism has tended to stifle the development of class stratification in its positive aspects: such as the improvements in agricultural technique made elsewhere under feudalism, that were driven by individual landowners' hunger for ever-increasing surpluses (39-41).

Another problem with the communalist form of property is that the drive to accumulation had to express itself in other ways for the elites of African states, some of them no less problematic than individual ownership in land. An important instance of this is the growing investment in slave labor by indigenous entrepreneurial classes, encouraged by communal strictures on private land ownership. In his major contribution to Atlantic Studies, Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, historian John Thornton explains that since members of the African nobility or state officialdom could not invest directly in land, they were deprived of an important first step in the formation of a modern bourgeoisie (80-85). But just because they could not become rentiers on the European pattern, they instead sought to increase their surplus through exploiting slave labor, typically (though not always) drawn from foreign peoples:

"If Africans did not have private ownership of one factor of production (land), they could still own another, labor (the third factor, capital, was relatively unimportant before the Industrial Revolution). Private ownership of labor therefore provided the African entrepreneur with secure and reproducing wealth....[Ownership of labor meant] slavery, and slavery was possibly the most important avenue for private, reproducing wealth available to Africans. Therefore, it is hardly surprising that it should be so widespread and, moreover, be a good indicator of the most dynamic segments of African society, where private initiative was operating most freely" (85-86).

This logic spurred on the internal slave traffic of the West African coast, driven by a local demand for slave labor that was distinct from (yet parallel with) the demand of European traders.

While Thornton's history of the slave trade consciously departs from Rodney's in many significant ways – most notably, in Thornton's judgment that African elites participated in the trade on a far more voluntary basis than Rodney's account suggests (Africa and Africans, 7), it is important to note that Rodney, too, identifies the coastal slave trade as a major industry in West African countries after the decline of the gold trade. Although his account continually stresses the overall deleterious effect on societies that had built themselves into major powers before their large-scale participation in the traffic of human beings (How Europe, 102).

Apart from the communal character of its economies, African historiography asserts that there were other challenges for large-scale surplus accumulation in Africa below the Sahara, placing us at a disadvantage in our later relations with Europe. Basil Davidson and Samir Amin both have pointed to the disintegrating effect that constant invasions and slaving expeditions had on the mega-states of the Sahel, which had formed a crucial link between West Africa and the world economy, through the Trans-Saharan Trade.

Davidson speculates that without its destruction by Moorish invaders in 1591,

"It is reasonable to think that [the empire of] Songhay would have continued with the long process of unification and civilization which had begun in the Western Sudan about a thousand years earlier. And here one may [state that] the Western Sudan, in this respect, was less fortunate than Western Europe. In his monumental study of European feudalism, Marc Bloch has underlined the key importance that outside invasions ceased to trouble Western Europe as early as the tenth century, and were never renewed except at the periphery" (Lost Cities of Africa, 120).

Another key development was the European "discovery" of the Americas, which displaced the world center of the gold trade from West Africa to Latin America (121). We will examine some consequences of this event for Africa's role in the slave trade throughout the remainder of this article.

Samir Amin, the Marxist economist and historian who developed his own non-Eurocentric framework for historical materialism, is also of the opinion that the fall of the Western Sudanese empires was fateful for Sub-Saharan Africa (Global History: A View From the South, 35-37). Because much of West Africa had remained at the communal stage of development, the survival of the Sahelian empires was crucial for their possibility of transition into a more advanced stage, that Amin calls the tributary mode of production.

Amin describes tributary societies in terms that are strikingly value-laden:

"[In antiquity], those zones in which there appears a marked development of the productive forces, allowing for the clear crystallization of the state and social classes, are isolated from each other. In this manner, over the course of a few millennia, Egypt, Mesopotamia, and then Persia and Greece are constituted in relative isolation... . These civilizations are islands in the ocean of the still widespread, dominant barbarity: that is to say, in a world still characterized by the predominance of the communal mode of production (as opposed to the tributary mode that typifies the civilizations in question)" (Eurocentrism, 105).

Leaving aside (for now) the questionable value-orientation of this description, let us note that tributary societies are characterized by strong centralized states, supported by tribute paid out of the surplus of an agrarian worker base; and that they allow for more specialized forms of labor, and for the greater elaboration of class distinctions than do communal societies. For Amin, the tributary mode is not an inevitable stage in the development of all societies. In fact it is historically quite rare; so that the destruction of the Sahelian empires, belonging to the periphery of the more advanced "Arabo-Persian Islamic centre" (Global History, 37), left Sub-Saharan West Africa especially ripe for exploitation by Western nations, which were already climbing out of the tributary and into the still more advanced capitalist mode of production by the Renaissance (a point to which we will return in Section III).

Without developing any detailed objections to Amin's position – a task for another time – we feel it is important to conclude this section with a corrective on the fetishism of the political state, once again with help from Walter Rodney:

"In some ways, too much importance is attached to the growth of political states. It was in Europe that the nation-state reached an advanced stage, and Europeans tended to use the presence or absence of well-organized polities as a measure of "civilization." That is not entirely justified, because in Africa there were small political units which had relatively advanced material and non-material cultures. For instance, neither the Ibo people of Nigeria nor the Kikuyu of Kenya ever produced large centralized governments in their traditional settings. But both had sophisticated systems of political rule based on clans and (in the case of the Ibo) on religious oracles and "Secret Societies." Both of them were efficient agriculturalists and ironworkers, and the Ibo had been manufacturing brass and bronze items ever since the ninth century A.D., if not earlier" (How Europe, 47).

To Rodney's examples can be added the advanced ancient civilization of the Niger Valley, centered on the city of Djenne-jeno circa 300 BCE, which engaged in iron-smelting and international trade without any apparent centralized state structure (Gomez, African Dominion, 13, 16-17). The necessary connection between a strong centralized state and a high degree of economic and social development, implicit in Amin's stagist construct of the tributary mode of production, is simply not as determinative as he would like.

What is clear from the foregoing discussion is that a general account of the economic character of precolonial Africa, of the "African mode of production," as Diop had called for, remains an unfinished task for radical historiography. Yet we can confidently say that in the Western Sudan, the Congo-Angola region, and elsewhere that an accumulation of economic surplus gave rise to monarchical state-formation, the overall tendency was toward national integration across tribal and geographic divisions. And while caste mediation (Part Three); communalism; and the essentially free-agrarian, rather than slave-based, character of pre-colonial economies, all acted as partial brakes on the growth of class antagonisms, that does not mean, pace Toure, that they were entirely absent from precolonial Africa. To the contrary: these antagonisms only needed the catalysts of foreign invasion and the rising slave trade to assert themselves boldly.

The next section is a detailed survey of the attempts by two peoples – the Malinke of ancient Mali, and the Mbundu of Ndongo, later Angola – to organize their dominions on a highly centralized state model, in order to defend against encroachments by foreign powers, and especially against slaving expeditions. Their astounding feats of regional unification and national defense disprove the colonial lie, that African people cannot excel at the highest level of statecraft. At the same time, because of their monarchical and inegalitarian character; their (historically) necessary adherence to policies of raison d'etat; as well as their (understandable, though no less tragic) inability to see in advance the shared interest of all Africans in unity, across ethnic and religious lines, these states were unable in the long run to resist the greatest threat to their independence, the organized terrorism of the European nations.

II. Contradictions of Statecraft in Medieval and Early Modern Africa

In 1324 CE, Mansa Kankan Musa of Mali, ruler of the largest empire in Africa, embarked on a famous hajj (Islamic pilgrimage) that impressed the known world with the wealth and power of the West African gold trade. In a procession of tens of thousands of subjects, the mansa (emperor) made his transit through the Maghreb; stopping in Cairo to consult with the Mamluk sultan of Egypt, one of the most powerful rulers in the world, before reaching his destination at Mecca. Along the way, he had distributed so many gifts of gold, that the mineral's value was reduced in the Mediterranean for nearly a decade after his return. It was the crowning moment on the world scene for the Western Sudan – a region of Atlantic Africa, extending from southern Mauritania to the forest belt in modern-day Ghana, where several famous capitals of trade, learning, and culture had developed for nearly a thousand years.

In a landmark study that upends many standard assumptions of West African historiography, Michael Gomez has argued that the earliest developed hub of the Trans-Saharan Trade was in Gao, in today's eastern Mali. This capital, known as Kawkaw to medieval Arab historians, boasted trade relations extending as far east as Libya and Egypt; its ruler reportedly owned at least two towns on the Nile River. Gomez suggests that Gao's role in the celebrated salt-and-gold trade of West Africa predates the Islamic era, stretching back perhaps some two hundred years before its regional hegemony is attested in Al-Ya'qubi's writings from the ninth century (African Dominion, 20-23).

But in African historiography it has traditionally been held that the basic pattern for the Trans-Saharan Trade was laid by Ancient Ghana, a kingdom of the Soninke people, that flourished between 800 and 1076 CE, in today's southeast Mauritania. The pattern was then adopted by the successor empires of the so-called Bilad es-Sudan ("Land of the Blacks," in Arabic) which loom large in the records of contemporary Muslim travelers, such as El Bekri and Ibn Battuta. From its capital of Kumbi-Saleh, Ghana controlled the transit of gold from the southern forest belt, north to the markets of Arab and Amazigh traders, in exchange for North African salt, which was in high demand among the forest peoples. From the Saharan Trade, African gold was then circulated throughout the Mediterranean and Europe; making the Western Sudan one of the world’s major suppliers of mineral wealth in the Middle Ages (Basil Davidson, Lost Cities of Africa, 82).

The king’s stranglehold on the gold trade was the source of Ghana’s splendor, but equally of its tragedy. In the twilight of empire, the king (Gana) could summon an army of two hundred thousand soldiers, as his contemporary El Bekri testified in 1067. Yet that imperial might was founded less on the military organization of the state, which was considerable, than on his trade monopoly with the hinterland; and his monopoly on gold in particular, which he guarded from his own subjects.

According to El Bekri:

“All pieces of native gold found in the mines of the empire belong to the sovereign, although he lets the public have the gold dust that everybody knows about; without this precaution, gold would become so abundant as practically to lose its value….The Negroes...known as Nougharmarta are traders, and carry gold dust...all over the place….” (African Civilization Revisited, 87)

What is most significant here is the influence of the trans-continental trade on Ghana’s fortunes. The king’s tax on foreign trade incited the Moors of North Africa, who controlled the Saharan salt mines, and wanted to cut through his armies in order to more directly access Wangara and other gold-bearing lands. So in 1054 the Almoravids, a military confederation based in Morocco, marched south into Ghana; and after fourteen years of plunder and Islamic conversion by sword, they had so thoroughly weakened the Ghanaian state that much of its territory fell to neighboring Sosso and Mali in the next two centuries.

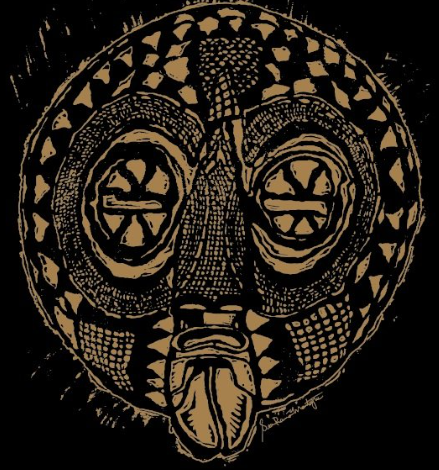

By the mid-13th century, Kumbi-Saleh, the last bastion of Ghana’s independence, was conquered by the Sosso people of Kaniaga, a former vassal state in the south-west of modern-day Mali. The Sosso conqueror, Soumaoro Kante, is remembered as a blacksmith, a member of the caste whose secrets of iron-working, when turned to the manufacture of weapons, made them a formidable military force throughout the continent. According to legend, Soumaoro was also an unscrupulous tyrant, a potent magician who used his powers to ravage and oppress his own subjects (Lost Cities, 87-88).

Sosso and Mali were two rising empires, competing to fill the power vacuum left by imperial Ghana. Both of their constitutions were based on a shared conception of life, yet the founders of their respective empires came from different castes and apparently subscribed to different faiths. In 1240, Sundiata Keita, the half-mythical founder of Mali and representative of the hunter caste, led his nation of Mandinka farmers to victory over the Sosso, ending the cruel reign of their blacksmith king, and inaugurating one of the most brilliant experiments in statecraft in world history. It is to that imperial project that we first turn.

"The Lion Has Walked": Recreations of History in Imperial Mali

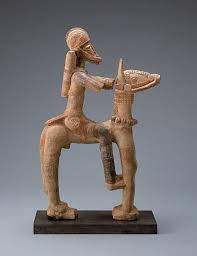

Sundiata, the epic tale of the Mali Empire's founding, was preserved in oral tradition for centuries by the djeli (historian) caste of the Mandinka. More than a linear account of national origins, it reveals the world-sense of the Malinke people, including elements of their cosmology, evidence of their shifting gender mores, and insights into the complex politics of caste, in a period of increasing Islamization and class stratification for the Manden peoples. To seriously discuss the society, culture and politics of medieval Mali, it is crucial to recall the main plot points of the epic.

Sundiata centers on the unlikely career of a young prince from the town of Niani, in modern Guinea, who went on to found the largest empire in Africa in the mid-13th century CE. Sundiata/Mari Djata I was apparently disabled from birth, being unable to walk or talk well past infancy. He was the child of Sogolon, described as an ugly and misshapen woman, given to his father by foreign hunters, who were told of her future importance by a shapeshifting witch they had slain.

Despite these inauspicious beginnings, Sundiata was expected to succeed his father as ruler of Niani, and ultimately to extend Mandinka hegemony over an enormous territory, spanning the length of the Atlantic Coast. Finally overcoming his disabilities in adolescence, and learning the secrets of the hunter guild as a young man, he soon became wildly popular with his people; renowned for his martial prowess, his wisdom, and his reputation for justice and honest dealing – all the desirable characteristics of a Mandinka monarch. But Sundiata was ultimately forced into exile by the intrigues of Sassouma Berete, an ambitious Queen Mother who maneuvered to install her own son as king, over his half-brother Sundiata, contrary to their deceased father's wishes (D.T. Niane, Sundiata: An Epic of Mali, 15, 18-19, 20-22, 28).

In his seven years of exile, Sundiata was welcomed into the royal courts of several powerful West African states, where he left a strong impression of his ability; including Tabon in modern-day Futa Djalon (Guinea), Wagadou (ancient Ghana), and especially at Mema, a Soninke colony in Mali. These experiences educated him in the arts of politics and warfare, that he would later turn to good use upon returning to Niani. They also expanded his geographic and cultural knowledge of the independent states that would later be incorporated by imperial Mali – a point to which we will return shortly.

During this time, Sundiata learned that Soumaoro Kante, "the great king of the day," had subdued his half-brother, Dankaran Touman, and made Mali into a tributary of Sosso. He also learned that Soumaoro was believed to be invincible on the battlefield, owing to powerful fetish magic practiced by the Kante blacksmiths; and that Soumaoro, an "evil demon," used his powers to violate every taboo in Manden culture with impunity. Finally, Soumaoro had reduced Sundiata's home town of Niani to ashes; revenge for a failed Mandinka revolt, led by Dankaran and Fakoli Koroma, a disaffected relative of Soumaoro (40-42).

With a small contingent of Soninke troops from Mema, Sundiata retraced his path of exile, gathering support from his former host nations on the way to meeting his redoubtable foe in battle. When he reached the enemy territory, his troops represented a cross-section of peoples from modern-day Guinea, Mauritania, and Mali: perhaps an index of Soumaoro's unpopularity with the nations under his control. Yet despite the superiority of Sundiata's coalition in their first encounter, at the Battle of Negueboria, the rumors of Soumaoro's dark magic had proved true. Not only could he not be wounded by arrows and spears, which simply bounced off his flesh, but he even had the power of teleportation, which he used to escape Sundiata's wrath (50-52).

For their second encounter, at the Battle of Kirina, Sundiata had other weapons at his disposal. His sister Nana Triban, a powerful magician in her own right, had previously been taken hostage by Soumaoro, who reduced her to a concubine. But she used her closeness to Soumaoro to learn the secret of his invincibility, and had escaped Sosso to inform her brother (57-58). Sundiata would finally defeat Soumaoro by grazing his flesh with an arrow tipped with the spur of a white rooster, the family totem of the Kante, which drained the tyrant of all his supernatural powers (64-65). Upon killing the great oppressor of the Sudan, Sundiata razed Sosso, and established the legendary empire of Mali in its wake (69, 82).

The account of Sundiata's ascension, and of the regional transition from Sosso to Mandinka hegemony, offers several clues about the character of medieval West African states, that are worthy of examination. But how historically reliable is this account?

In the first place, it should be kept in mind that the Sundiata epic was formalized in the 17th century CE, under the reign Mansa Saman – that is, several hundred years after the decline of Songhai, the successor state of Mali, which was the last Sudanic empire on Mali's model and scale. It must be appreciated that by this time, Mali's sovereignty did not extend any further than the small state of Minijan; and that the non-Muslim Bambara, their long-standing rivals for Manden supremacy in the region, now controlled much of modern-day Mali, from their capital at Segu (Gomez, African Dominion, 65).

So while the Sundiata tale does consist of simple plot elements that were accurately retained in song by generations of djeliw, its articulation in a linear epic form is therefore a much later development than the events it describes, and one that is by no means politically innocent. Not only is the epic hagiographic – and understandably so, given the nostalgia of declining royalty for Mali's heyday. But its collapse of then-contemporary with ancient attitudes also obscures the difference made in Malinke values, in the intervening centuries, by the complexly contradictory process of empire-formation.

In fact Malinke society and culture underwent drastic changes within just the first decades of imperial statecraft, prior to its long era of decline. Those changes centered on its state-directed process of Islamization, and on the related challenges of the Trans-Saharan Trade; dominated in the North by co-religionists with shifting political and theological commitments on the world stage; who in addition were of a different and often hostile race, ill-disposed to accept the Islam of Black Africans as the genuine article. Those changes also followed from the need to justify an expansionist policy at the expense of non-Malinke peoples; and on the contradictory policy of slave-raiding jihad against non-Muslim Africans, and increasing reliance on slave labor at all levels of society.

Drawing heavily from Gomez's brilliant revisionist study of the Western Sudan, we will now discuss these contributing factors to Mali's dialectic of decline, before turning our attention to statecraft in the Angolan context.

While the Sundiata epic lays a litany of foul charges at Soumaoro Kante's feet, one of the more interesting accusations gets perhaps less attention than it should. That is the charge of idolatry. In his version of the epic, D.T. Niane mentions the matter of Soumaoro's rejection of Islam almost in passing:

"At the time when Sundiata was preparing to assert his claim over the kingdom of his fathers, Soumaoro was the king of kings, the most powerful king in all the lands of the setting sun. The fortified town of Sosso was the bulwark of fetishism against the word of Allah. For a long time Soumaoro defied the whole world" (41).

Immediately his "fetishism" is tied to one of Soumaoro's more disturbing practices; and then an explanation consistent with Islamic beliefs is given for his magical potency:

"Since his accession to the throne of Sosso he had defeated nine kings whose heads served him as fetishes in his macabre chamber. Their skins served as seats and he cut his footwear from human skin. Soumaoro was not like other men, for the jinn had revealed themselves to them and his power was beyond measure" (41).

One wonders if any parallels with the kaffiruun (unbelievers) of their own day would have leapt out at a Malinke audience in the 17th century, since the Bambara of Segu were also "fetishists," with unaccountable power over lands which by rights belonged to Muslims. What holds our own attention in these passages is their evident anxiety over the polytheistic character of traditional Africa, and the connotations of barbarity that so casually attach to them. This is not incidental, but is part of the underlying tension between indigenous and cosmopolitan forms of Islam as practiced in West Africa.

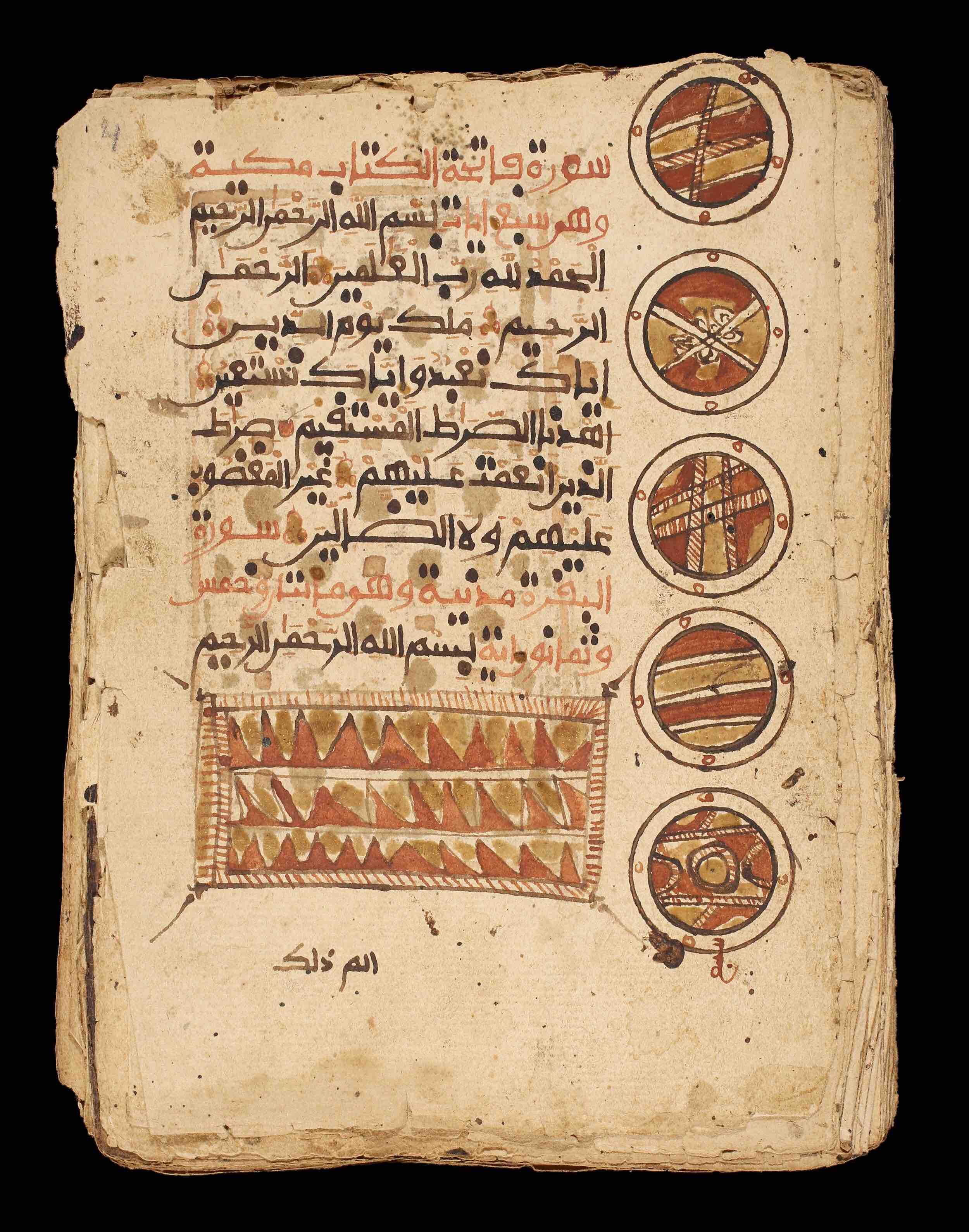

The Islamization process of the Western Sudan, which facilitated trade with the Arab and Amazigh traders of the Maghreb, took place in several stages between the eleventh and nineteenth centuries. Generally these followed two paths. The first is syncretic Islam, which was the form most widely practiced by early converts in West Africa. Syncretic Islam tries to synthesize Islamic articles of faith and certain conventions of everyday ritual (such as prayer, veneration of Qur'an, dietary prohibitions) with familiar elements from pre-Islamic cosmology, ethics, and social conventions. If Sundiata Keita was in fact a Muslim, this is most likely the form that his belief took. (That would explain some of the "fetishistic" elements of his victory over Soumaoro.) Today, syncretism can be most easily seen in the practices of heterodox sects like the Baye Fall of Senegal, who do not observe regular prayer, and indulge in marijuana for spiritual purposes; and in the careers of various "fortune-telling" marabouts who are spread across West Africa.

The second path is reform Islam, which attempts to purify local Islamic practices of all corrupting, pre-Islamic elements in non-Arab cultures. Reform Islam in the West African context is widely held to begin in earnest with the campaigns of the Almoravids of Marrakesh against the Soninke, culminating in the aforementioned fall of Ancient Ghana in 1076. However, Gomez postulates an earlier, more local origin, citing the military victories of the indigenous ruler Warjabi bin-Rabis (d. 1041 CE) against the "idol-worshiping" peoples in the middle Senegal Valley. The career of Warjabi, whose jihads helped establish the Islamic state of Tekrur as a major entrepot on the Senegal River by the 12th century, was quite possibly the political inspiration for Yahya bin-Ibrahim, founder of the Almoravid sect. Gomez notes that Yahya, originally based in southern Mauritania and in close touch with developments in the Sudan, only began his jihads eight years after Warjabi's passing, though most histories treat the rise of the Tekrur state as a by-product of later Almoravid conquests further north (36-37).

If true, what this establishes is that reform Islam as an ideology of conquest, exemplified by the Sokoto Caliphate of the 19th century, is not historically speaking a foreign imposition on West Africa. For better or worse, it emerged on its own, from the puritanical zeal of West African elites. Which is not to say that they did not expect improved relations with powerful allies in the wider Ummah (global community of Muslims) in return for their tokens of faithfulness.