It Was Never About Law And Order

"It has been made abundantly clear by this and many other situations that 'law and order' has always meant playing to the racial fears of the white majority."

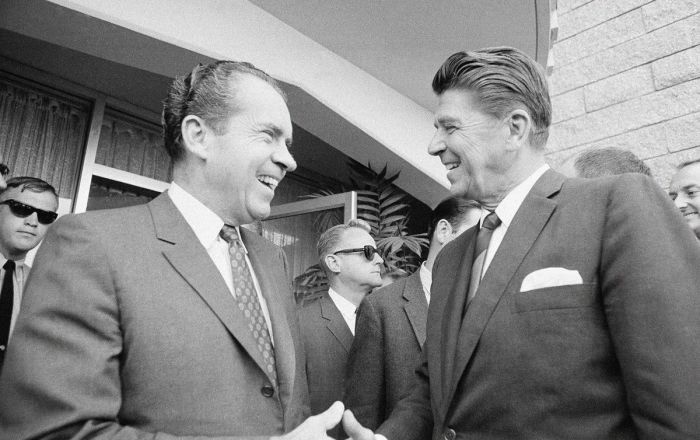

In 1968, Richard Nixon was taking the stage of the Republican National Convention. He had positioned himself as the “law and order” candidate, promising to return the United States to an era of peace and prosperity; to put an end to the social strife that was ravaging the country as the Vietnam war raged on and the civil rights movement pushed forward against intense opposition.

That second point was key. While war fatigue was setting in across the country, the demographic Nixon was aiming for still believed in the cause. American exceptionalism was at an all time high; the meteoric rise of the US, from a nation in grip of a severe economic depression to an international powerhouse, was still fresh in the memory of the older generation, and a new generation was taking the reins after coming of age in a time of unparalleled economic prosperity.

But this time of plenty was tempered by other events. The civil rights movement had forced the happily oblivious majority demographic to confront the ugly reality that the “land of the free” came with some stark caveats buried in the fine print. Additionally, a sympathetic youth counterculture was rallying behind them, shaking up the assumed order and challenging the validity of traditions held unquestioningly sacred until then.

It was a fraught time, and as usual during such times, a strong reactionary movement began to build. Rather than seek to understand the cause of this strife, the privileged majority was more interested in making it go away. Cue Nixon, the inheritor of Barry Goldwater’s mythic reinvention of modern conservatism.

Goldwater had keenly pinpointed the glaring weakness in the emergent neoliberal Democrat party: by embracing the legacy of Franklin Roosevelt and rallying behind Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society initiatives, the Democrats were trying to make themselves the party of the minority – of extending a hand to those previously ignored, in the hope of bringing them into their camp. Goldwater cynically played on the old adage that “equity feels like inequality to the privileged.” He knew that such controversial initiatives like desegregation and full voting rights would enrage a previously complacent electorate that would be eager for direction. Goldwater and the party royalty that would follow him were more than happy to provide.

History has shown that no great social sea change comes without conflict, and it was decidedly easy for neoconservatives to make their tentpole a strong opposition to the riots and civil disobedience that characterized the antiwar and civil rights movements. But they had to be canny about it; rather than protesting the causes, they would instead go after the methods. Hence, “Law and Order,” Nixon and his party didn’t, on the surface, oppose integration and voting rights, they just opposed how the protesters were making their voices heard. On the surface, they understood the antiwar movement’s anger, they just didn’t agree with the methods with which they expressed it.

But buried beneath that innocent veneer lay a coded message to those with an eye for it. A “return” to “a time of law and order” meant a return to when “people knew their place.” A return to when the country knew the peace of ignorance and the comfortable didn’t have to confront the origins of their comfort. These tactics of saying one thing with a wink and a nudge to communicate something else were nothing new. In fact, they were all too familiar; they were a favored strategy of the far right parties that had ruled Germany and Italy just a few decades prior.

It is through these methods that people can unconsciously find themselves edging more and more into a fascistic line of thinking. Fascism preys on those who desire an authority figure to give them direction and purpose. Who find comfort in standing shoulder to shoulder with others unquestioningly united under a common purpose and shared tradition. Seeing someone stand on a stage saying that they too see the violence, they too feel the “wrongness” pervading the nation – and they’re going to make it stop – is an intoxicating combination.

Neoconservatism would follow this line into the 21st century. Lee Atwater would famously confide to an interviewer in 1981 that as society progressed it became necessary to code one’s language when speaking to the public, saying essentially that since it was no longer acceptable to say things like the n-slur in public, one had to attack the tangential things that would still victimize minority demographics first:

“So you say stuff like forced busing, states’ rights and all that stuff. You’re getting so abstract now you’re talking about cutting taxes, and all these things you’re talking about are totally economic things, and a byproduct of them is blacks get hurt worse than whites.”

Ronald Reagan would codify this in his development of “Reaganomics,” (a program still lauded by conservatives today) making “states’ rights,” “tax cuts,” and cutting off “welfare queens” pillars of his platform. Atwater would remain a mover and shaker in the modern conservative movement through the Bush years, serving as a strategist on H.W.’s campaign along with Roger Ailes, who was better known as the longstanding chairman and CEO of Fox News.

It would all reach its cartoonish apotheosis in Donald Trump. Kicking off his campaign by invoking the boogeyman of the “illegal immigrant” bringing drugs, crime, and rape into the United States, he vowed to restore “law and order” to the nation by expelling them.

While his campaign was met primarily with derision from the center-left, the joke became less and less funny as the years wore on. Because what was missed behind all the bluster and madcap bigotry was something that was all too familiar to those who hadn’t lived the sheltered existence of the neoliberal middle class. Trump was holding up all of conservatism’s greatest hits, just stripped of all their pretty veneer. And even raw, that was going to speak to the masses. In fact, it was going to tell them the time had come to take the kid-gloves off.

And if his rhetoric didn’t make that clear, his actions did. Again, under the guise of “restoring order,” Trump gave the greenlight for immensely cruel racially-based initiatives, culminating in the systematic abduction of undocumented immigrants across the country.

The hypocrisy and true purpose of these programs was laid bare just a few weeks ago, when a Koch foods plant in Mississippi was raided and hundreds were taken away. Despite knowingly employing hundreds of people illegally, and having been fined for doing that exact thing before, Koch foods has, as of this article's writing, faced no penalty for its actions, and even had the audacity to have a hiring fair the next week after the raid. It has been made abundantly clear by this and many other situations that “law and order” has always meant playing to the racial fears of the white majority.

At the end of the day, that’s what this was always about. White supremacy pervades American society; there’s no way it couldn’t, considering its founding. And conservatism in the United States has always been about the cynical harnessing of white supremacy for the sake of consolidating power. Everything Donald Trump has done is no different from what has been done for decades past. The only difference is he lacks either the finesse or the patience to do it without waking the dragon. The plan was always to stoke the fire, but never let it get out of control. There has been no public outcry because the only sin he has committed in the eyes of the establishment is throwing off the disguise.

The Democrat party is hardly innocent in all of this. Just as Hillary Clinton faced intense scrutiny over her pushing of the “super-predator” narrative in the 90s, Democrat front-runner Joe Biden now faces difficult questions about his opposition to integration busing and his role in drafting the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, a keystone in the Democratic party’s attempt to gain the “law and order” vote.

So, what can be done? The first step to solving a problem is admitting you have one, and this is a ripe time to do exactly that. The Trump presidency has stripped away the “respectability” of neoconservatism and laid bare the ugliness that always lay beneath. The people of the US need to take a hard look at it and not reject its truth or deflect from it. Erasure of sins only makes it more likely future generations will repeat them, and ignorance of history makes it impossible to see the foundations that systemic inequality is born from.

Another is learning to recognize subtext, and seeing beneath the surface level rhetoric of politicians. When someone talks about enhancing states’ rights, they really mean subjecting the minority to the tyranny of the majority. When they talk about “shrinking entitlements,” they really mean eliminating social safety nets that millions facing generational poverty brought about by systematic oppression need to survive. Politics is not an abstract or a thought experiment. When services are removed, when protections are lifted in the name of hypotheticals, people die.

This lens must be held up against the left and right establishment equally, because in the rise of Trumpism, the system has not failed, the system has only been exposed. And it is only by recognizing that the problem is that things are working exactly as intended, that we can begin to change it.